Bad retailers will never run out of customers – history suggests that there is always a segment of the consumer population willing to ‘trade down’ if they believe they can save a dollar or two.

Some retailers, like long-beleaguered US department store JC Penney, have spent decades proving this thesis.

No, bad retailers will never run out of customers, but they will run out of support from brands, and the reason for that comes down to simple maths.

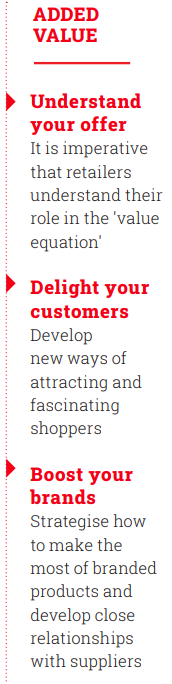

At its core, retail has always been a value exchange between brands – that is, the businesses that manufacture branded product lines – consumers, and retailers, with retailers occupying the precarious middle part of the equation.

For the relationship to hold, each party must contribute value to the others, leaving all feeling richer.

But in a post-industrial, increasingly post-digital, and post-pandemic world, the retailer’s place in that equation has become more complicated.

The value equation

Only a decade or two ago, delivering value as a retailer was relatively simple.

Brands brought product design, quality, and name recognition, while consumers brought demand and dollars.

And retailers, in most cases, needed only to provide physical points of distribution for products, coupled with a willingness to relay product information on behalf of the brand to consumers.

Everyone was satisfied – until now.

The problem today is that while the value contributed by brands and consumers has remained more-or-less constant, the contribution traditionally made by retailers is now all but worthless.

Consumers, with the internet at their fingertips, no longer require retailers to act as porters of product information.

Likewise, brands, with unmitigated digital access to hundreds of millions of consumers, no longer need to rely on a third-party retailer’s physical assets for customer acquisition or product distribution.

In other words, consumers and brands have all the tools they need to carry on quite capably without retailers.

Hence, brands like Nike are ramping up their direct-to-consumer strategies and dispensing, to a large extent, with wholesale.

It has all driven us to a rather dramatic moment in retail history; a point where retailers across all categories have to completely re-think the value they bring to their part of the equation.

They must once and for all retire easy scapegoats like Amazon, e-commerce and Millennials because the real enemy is none of these external forces, but rather their own failures to beat back irrelevance, a condition for which there is only one cure – reinvention and the contribution of new radical value, not only for consumers but for brands, too.

Defining ‘radical value’

This notion of radical value is important.

Take, for example, Amazon. Love it or not, brands are drawn by the tens of thousands to sell on Amazon because Amazon radically redefined our sense of selection and convenience and in the process, formed a global tribe of Prime Members nearly 200 million deep.

Similarly, China’s Alibaba has executed a radical level of integration into the lives of its customers, offering brands access to the world’s largest single market of shoppers.

In order to survive, all retailers must create similarly radical levels of value.

It starts with creating radical value for customers. Retailers can and must create radical value in one or more of four areas:

• Cultural value – Outdoor clothing retailer Patagonia creates radical cultural value through its single-minded focus on environmental stewardship, placing this imperative at the core of everything the business does including its financial model.

This makes Patagonia as much a social movement as a retailer; the commitment to the environment acts as a lightning rod for likeminded customers and staff.

All organisational objectives, communications and initiatives ‘ladder’ back up to environmental protection, making Patagonia a ‘tribal ‘outpost for customers who share its values.

• Entertainment value – Retailers can also create customer value with entertainment; UK department store Selfridges creates radical entertainment value through an intense focus on experience.

From streetwear departments with skate bowls to creative pop-ups and unique food and beverage installations, the experience at Selfridges has, to a great extent, become the product itself.

The years leading up to the pandemic saw the retailer make huge investments in what managing director Andrew Keith recently called “all the magic that goes on in the store”.

• Expertise value – I am an advisor to New York’s Allure Store, which is a partnership between Condé Nast – which publishes the beauty magazine of the same name – and retail platform Stour.

This store delivers radical expertise value in its category – beauty products – through authority. This authority is established via the staff.

The Allure beauty store does not hire retail workers who then become experts in beauty through training, but instead hire beauty influencers looking to broaden their reach through retail.

The result is a dynamic team of influential beauty experts, all of whom speak with authority from personal and professional experience and do so both with customers in-store and through social content shared to the retailer’s growing legion of followers.

• Product/channel value – Finally, there are those retailers that bring radical levels of product design, channel control or consolidation to the table.

Luxottica, for example, is estimated to control 40–60 percent of the global eyewear market, making it almost impossible to do business in the optical category without doing business with Luxottica.

Retailers that so thoroughly control access and distribution within a category carry obvious value to consumers as a go-to destination.

Other retailers create products that become so dominant in their categories that they become a magnet for associated products.

Apple is one obvious example; if you manufacture iPhone cases or any other tech accessory, chances are you’d clamour to obtain space in an Apple store because Apple contributes radical levels of design to both its products and its stores.

Value creation for retailers

Businesses often make the mistake of trying to sell to everyone – but why exactly is this a mistake?

Businesses often make the mistake of trying to sell to everyone – but why exactly is this a mistake?

What’s particularly interesting is that, in most cases, the same retailers that create radical value for consumers also tend to create equally radical levels of value for the brands they stock.

In becoming a cultural flagbearer for the environment, Patagonia brings to its ‘brand partners’ an army of loyal and highly-engaged customers to whom they otherwise wouldn’t have such easy access.

Another example is the US retailer Camp, which sells children’s toys, activity sets, books, and more.

Camp creates elaborate in-store theatre and events for parents and children, marketing itself as a ‘family experience company’.

In doing so, the business provides hands-on and contextual opportunities for children to engage with brands’ products; opportunities that simply can’t be delivered online or in other more conventional toy stores.

B8TA is arguably one of the most successful retail start-ups in the market, bringing an entertaining and tightly-curated selection of products to their customers – products not easily found elsewhere.

Not only does the business attract a particularly passionate segment of the market, but its model is based on in-store product demonstrations and presentations.

Manufacturers pay to rent out space for their product to be displayed inside B8TA’s retail locations, along with a tablet that each brand customises with software.

This model offers the manufacturers access to a robust data set, providing them with consumer intelligence and insights they wouldn’t otherwise access.

Similarly, the Allure Store not only delivers an authoritative level of beauty expertise to their customers – as mentioned previously – but also acts as a marketing ‘fly-wheel’ for brands, producing radical levels of compelling product content and in-store activations, all of which would carry significant cost if brands were to produce it themselves.

The common thread here is that these retailers are fundamentally changing the conversation they’re having with brands.

For too long, we’ve assumed the retailer-brand relationship to be transactional – purely based on volume, margin, and incentives.

But brands today are asking for more; they want market intelligence, they want – at the very least – ‘co-ownership’ of the customer relationship where loyalty is shared, they want their unique ‘brand story’ articulated and animated with excellence, and they want their prices treated with integrity.

Retailers that appreciate this shift and deliver radical value back to brands will perform better in the long-term than those retailers who do nothing but extract value from the relationship.

Because, in the end, retailers that do not become a source of radical value for brands will awaken one day to find their sales floors empty of branded goods.

READ emAG