Incidentally, in later sponsored industry reports this was glossed over.

Producers were praised as to how their “response at the start of the COVID-19 crisis helped mid-stream players weather the worst of the storm”w by cancelling sales and allowing clients to postpone rough purchases.

Talk about making a virtue out of a necessity!

However, in retrospect, it does look like it helped the industry get on its feet much faster.

It is illuminating to see how the estimated rough stocks in India as a whole moved over the past two years.

As mentioned, October 2019 was the end of the destocking cycle, and we can consider that to be the ‘zero line’ and look at the stocks (see Chart B).

As can be seen, by March 2020, stocks had nearly risen to their 2019 peak, in anticipation of the 2020 sales, before dropping during the moratorium period. These again started climbing, and seem to have reached the peak levels again.

The health of the mid-stream is determined by the polishing profitability and, more critically, diamond prices. Typical polishing margins in the businesses are in the low single digits and hence a 10 per cent drop in stock price can wipe out years of business gains.

The rough moratorium helped the mid-stream ensure that the liquidity pressures were limited, as there was no rough, and no stock, to be financed. This, in turn, reduced the pressure on companies to have to sell at any cost – ensuring that the price of polished [goods] did not crash when the market was illiquid, preventing a serious balance sheet crisis for the mid-stream.

As the retail sales grew from strength to strength, replenishment orders started filtering through.

The Indian mid-stream had destocked sufficiently by August and started buying rough to ramp up their production to meet the ongoing sales demand.

With large rough producers following a price-versus-volume strategy, the offtake started a little slower, before picking up steam.

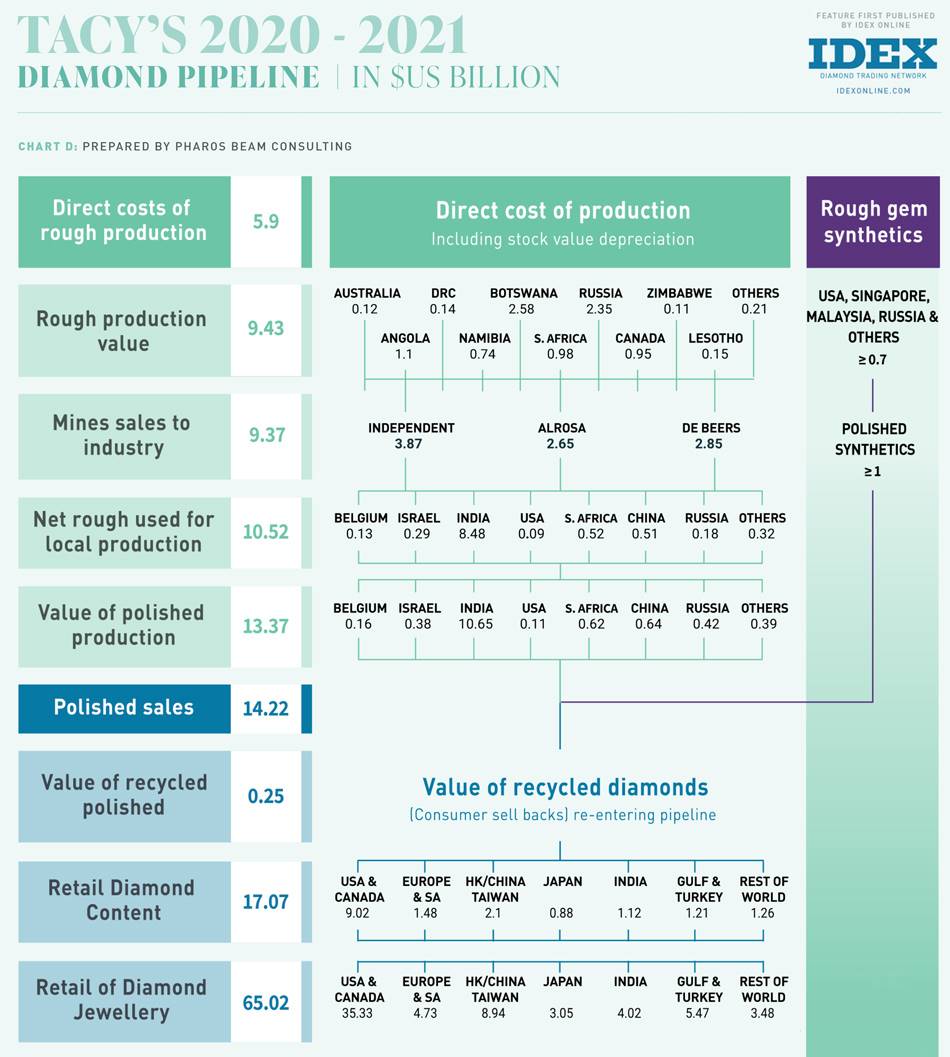

The mid-stream managed to sell about $US14.2 billion of polished, or about 20.7 per cent below 2019 sales, despite 2019 itself being considered a lousy year for retail.

Mid-stream deleveraging

As mentioned, stock prices can make or break the balance sheet of the midstream, and the actions by the mid-stream ensured that the price drop remained within an acceptable level.

The retail surge also meant that by the end of the year, overall diamond prices were almost at par with those at the end of 2019, if not higher – a remarkable achievement, considering the chaos of the second quarter!

As with retail, the mid-stream too brought in additional efficiencies into their operations, including pruning of the workforce as well as reducing travel and marketing expenses.

This was certainly helped by the fact that industry shows and events could simply not be held due to the COVID-19 restrictions in place.

The pickup of polished demand also allowed the mid-stream to destock. During the destocking process, as inventories are liquidated, bank lines are repaid, leading companies to reduce their borrowing.

Our estimates show that the industry was able to reduce its borrowing by nearly 20 per cent during the course of the year, driven by a neverbefore-seen combination of destocking and better profitability – in the second half – with almost no stock loss being booked!

We believe that the industry leverage is probably at the lowest level – even better than what it was at the end of 2011, which was the standout year for the industry in recent memory.

As a result of the destocking, rough sales by miners dropped by about 36.7 per cent and clocked in at about $US9.37 billion for the year.

Rough producers – saved by the bell?

Producers had weathered a rough 2019, as the mid-stream deleveraged and rough purchases dropped to the lowest level in a decade.

With good sales recorded in the 2019 season, rough diamond sales were looking up and rough producers were looking to make up lost ground, until the pandemic struck them hard by mid-March.

As mid-stream ground to a standstill, and the Indian moratorium kicked in, almost no rough was sold for about two to three months. For a few producers who were already facing serious headwinds and profitability issues in 2019, as well as those with a high leverage, this proved to be the final straw.

They had to go in for temporary mine closures as well and also rework their financing agreements. This forced these mines to stop production for an extended time during the year, at least until they were able to do the necessary restructuring.

In a way, this forced reduction of supply eased the pressure on the two leading players to cut production.

Among the larger producers, generally most of the mines were able to operate, except for short periods if COVID-19 cases were detected in a specific mine.

While they continued to operate at slightly lower production levels, the impact of lower production was mainly limited to Q2.

The mid-stream actions in Q2, lifting of lockdowns and the sustained consumer demand in the second half of the year significantly revived the diamond markets, and secondary market box premiums by end of 2020 – and continuing into 2021 – provided testament to the enhanced rough demand.

Interestingly, the two leading producers seem to have taken a contrasting view on their production strategies during the year

De Beers produced about 25 million carats, while selling about 20 million carats during the year, and stockpiling the remaining production. A major chunk of this stockpile has been sold down during the first quarter of 2021.

Alrosa, on the other hand, came into 2020 with a sizeable stockpile from 2019 and for 2020 produced only about 30 million carats while selling about 32 million carats, meaning that they actually were able to reduce their stockpile during a year of rough sales!

It shows that Alrosa was quicker on the gun, and decided to prioritise sales in the latter half of 2020. Alrosa was able to get within breathing distance of De Beers’ rough sales for 2020, with the last four months of 2020 accounting for about 55 per cent of the sales for the year!

A look at projected production shows that Alrosa is forecasting production to be lower than De Beers, which seems inexplicable, especially given that Alrosa rough sells at a lower price and that they generally produce about 30 per cent more than De Beers.

The lower projected production has the potential to destabilise rough prices in certain categories of rough in 2021, but we believe that Alrosa will significantly increase their production target for the year, as they do have the spare capacity for the same.

|

| Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce |

Lab-grown story – growing into its own market

Lab-grown diamonds are an integral element of the diamond pipeline, at least at the retail level.

While there might be some overlap between the polishing as well as polished and jewellery wholesale areas, these are still distinguishable.

At the retail side, while there might be a few exclusive outlets or websites, generally lab-grown diamonds are starting to find a foothold in a larger chunk of the jewellery stores, at least in the US, where the category is the most mature.

The lab-grown retail market is still very much in its teenage growth years, with many brands trying to establish themselves. Competition is still about market penetration and spreading the distribution across the markets, along with filling the pipeline.

It is to be seen how many survive over the next five years. While the retail growth shows promise, it still is very much a stocking demand.

Overall, lab-grown diamonds grew in market share during the year, simply because their demand is primarily dependent on the US and did not drop as much as that for natural diamonds.

The technology is showing signs of maturing, with quality differences in the products narrowing. At the current stage, the ‘patent wars’ in the lab-grown industry are being fought, with all parties trying to get a competitive advantage over their competitors.

De Beers had a mixed victory over IIA Technologies in Singapore early last year, while recently WD Lab-Grown Diamonds lost a lawsuit against Fenix in the US.

The bulk of the rough lab-grown diamond production continues to come from the HPHT [high-pressure, high-temperature] process, dominated by the Chinese industrial producers.

The bulk of the value comes in from the CVD [chemical vapour deposition] production, which gives better and larger stones, and that production is more widespread, with capacities being set up in India at a fast clip.

Industry performance sustainable?

There is no doubt that the industry has performed spectacularly at a retail level over the past six months and is witnessing one of the best periods for the industry. In June, many traders were reporting that they had never been as busy as they currently were.

Our current favourite indicator for midstream activity and health is undoubtedly the backlog at the grading laboratories. A longer delay signifies increased activity levels in the mid-stream, and even on that count, the industry seems to be doing swimmingly!

However, there is a difference of opinion in the industry. On one hand there is unbridled optimism with claims of the industry outperforming others and that it has been able to better engage with the customers and even attract Millennials during the crisis.

On the other side, we have other industry leaders and media saying that this is a flash in the pan and the market will slow down going forward.

Even the leading retailers in the US have struck a cautious tone about future sales, despite record-setting numbers in the first half of 2021.

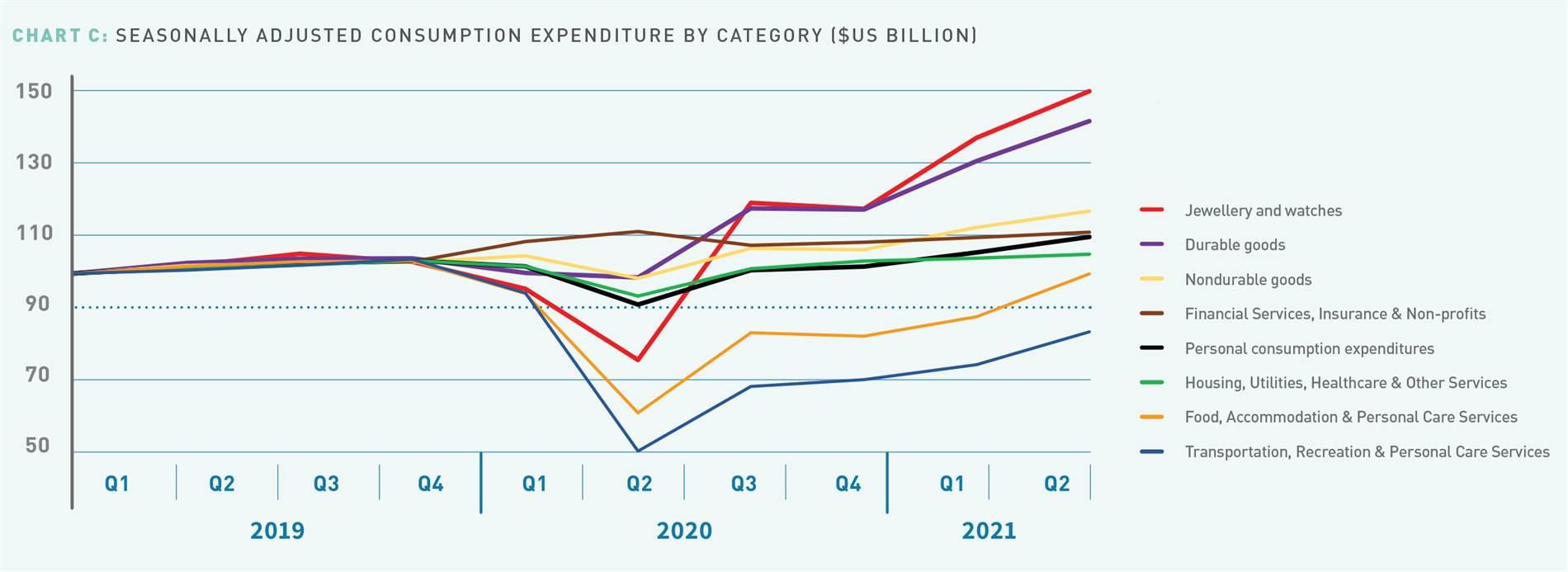

To understand whether we, as an industry, have truly outperformed, we can once again look at the US market data from the US Bureau of Economic Affairs (see Chart C).

In analysing any data, the inherent seasonality of any demand proves to be a challenge, as the annual pattern of each industry varies. However, the seasonally adjusted consumption expenditures data does this for us and is a useful gauge of how the personal consumption has changed over the period.

What we would specifically like to do is to compare the jewellery industry performance with that of other goods and services. We have grouped together some services for it to better reflect the comparison and impact of the pandemic.

The data has been presented at a quarterly level so as to damp out any monthly fluctuations, and focus on the overall trends.

There are some interesting observations which can be made on the trends:

There are some interesting observations which can be made on the trends:

• The pandemic and the resultant lockdowns to contain it affected overall movement and activity in the economy, which is visible in the dip in the second quarter. Currently the personal consumption index is about 10 per cent above that of the 2019 Q1 baseline.

• As we all know, the service industries were most affected by the lockdowns and travel restrictions, and these include transportation, recreation, personal care, food, and accommodation services.

• Housing, utilities, healthcare and other services have held steady during this period. These are the basic requirements and would be expected to do so. This block accounts for 40 per cent of the overall personal consumption expenditure in the economy.

• While non-durable goods have shown a good increase, durable goods have by far outperformed other categories of consumption. US consumers seem to have a new- found love for acquiring physically durable products.

While the jewellery category does stand out as the best performer in this chart, it is to be noted that the industry’s performance is in line with that of other durable goods.

If you dig down deeper into the data, you will find categories like motor vehicles – a much larger industry – have outperformed jewellery.

Even other industries of comparable size – be it sporting equipment, guns and ammunition or sports and recreational vehicles – have performed better than our industry.

Clearly, while the industry is among the better performers, it is simply part of the ‘gold rush’ of consumers as they spend on acquiring durable goods.

It can be argued that consumers, who had saved from not spending on the services mentioned above – as well as buoyed by the handouts provided by the government – channelled a large chunk of their excess funds into buying the physical durable which they had longed for but had not been able to buy.

Additionally, the wealth effect of the stock market boom, fuelled by government stimulus and ultra-loose monetary policy, also helped loosen the consumer purse strings.

This also makes sense because durable goods are generally more expensive, last much longer, and have a utility value over their lifetime.

There is no doubt that diamonds and jewellery have more of an emotional element in their purchase decision. During a crisis, and the pandemic is no different, humans do look for emotional connection and jewellery is simply a beautiful way to express it.

It is natural that couples who have been stuck at home during the last year have bought jewellery to express their love!

The return to normalcy is not going to be a sudden one, unlike the onset of the pandemic. As vaccinations across the globe are slowly rolled out, businesses will gradually revert back to the previous behaviour over the course of the next two to three years.

As disposable income reduces with travel and other areas becoming prominent again, and the experiential luxury market gradually increases, the share of the wallet will again shift out of the jewellery category – something which the industry should not give up without a fight.

A similar trajectory is playing out in other major markets like China and India as well as other luxury categories.

Consumers are spending their excess disposable income on these categories and it would take two to three years for the market to reach the ‘new normal’.

Looking forward

The authors had, in the 2019 pipeline article, mentioned that 2021 would be a very good year for the industry, with rough and polished sales expected to between the 2018 and 2019 levels.

The sustained retail boom in the first half has meant that the performance is likely to be even better, barring any sudden crash of world economies.

We expect that the polished sales for the industry would clock in at about $US20–21 billion, while the rough sales should come in around $US17 billion, with De Beers and Alrosa accounting for about $US10–11 billion.

It is likely that the current market euphoria will continue into Q4, before quieting down by the end of the year.

While this much is clear, prices on the other hand, are a representation of the demand-supply mismatch. With a healthy demand and an absence of supply, prices would, per force, rise.

In the initial phase of every upcycle, prices remain stable, as producers run down their stockpiles to meet demand.

We are currently in the latter phase of the cycle, wherein most producers would have exhausted their built-up supplies, and the increased demand would directly reflect in the prices.

Recent history has taught us that the best prediction for the end of a boom cycle is clearly a sharp increase in prices and euphoria in the rough market – though we are not there yet!

In our industry, a good year always sets the stage for the next year’s underperformance.

Traditional wisdom has it that when the going is good, strap in and get ready to ride the rollercoaster, because 2022 will be a different story!

In a market where producers still can manipulate the supply and demand fundamentals, the pandemic remains fully out of control – in spite of governmental assurances stating otherwise.

This is an edited version of an article that was first published by IDEX Online in August 2021, and is reproduced with permission. Visit idexonline.com.

READ emAG