It is well known that in 2021, the diamond midstream and downstream sectors experienced what was probably one of their best years in recent memory, right up there alongside 2011.

It is well known that in 2021, the diamond midstream and downstream sectors experienced what was probably one of their best years in recent memory, right up there alongside 2011.

In the euphoria, US$20 billion of potential and thus unearned income was lost as a ripple effect of the legitimisation of laboratory-grown diamonds (LGDs) by

De Beers. High Street jewelers and high-end jewellery chains, traditionally the greatest defenders of the natural product, have lost their inhibitions and are now the main LGD drivers, without reputational fears.

Nevertheless, the entire industry not only saw a surge in sales after the COVID outbreak in 2020, but also experienced one of its most profitable years, something for which it had been yearning. 2021 helped the industry ‘right-size’ its inventories and bring the overall business model back in line with what it should be.

De Beers, champion of the natural diamond industry, triggered the universal acceptance of the competing LGD product with the launch in 2018 of its Lightbox range of diamonds. It’s now apparent this move heralded a point of no return for the massive uptake of the LGD industry and the natural diamond industry will now have to live with the implications.

Those who have followed our annual analysis for many years will remember that we have said that eventually the price differentiation between natural and LGD will disappear, and the market will know only one product, called diamonds. Fortunately, we aren’t there yet!

With the launch of Lightbox, De Beers management said they hoped to keep LGD prices in check and to corral LGD into the impulse-purchase category. All this was backed by a lot of research.

The reality is quite different; a bulk of LGD sales now cater to the bridal market! Just read one of many headlines on bridal websites: ‘These are the best places to buy lab-grown diamond rings’, or ’Maximise your budget without sacrificing style’.

We find it difficult to believe that De Beers’ research missed this outcome.

Pricing policies in natural and LGD diamonds are not all that different. The bulk of LGD sales by value are in the larger stones (pointers and carat-plus stones) and if

LGD stones were sold at natural prices, the size of the diamond pipeline would probably nearly double from $US22 billion of polished sales to $US40 billion.

While it can be argued that it might not necessarily be a correct comparison, it highlights how big a dent the LGD market has made in the natural diamond industry.

It is just a matter of time before countries that produce natural diamonds fully realise the irreversible damage the legitimisation of LGDs has caused to the natural diamond pipeline. In any case, it’s probably too late for Botswana and Namibia to rebel against De Beers.

That is, the producing countries have also seen a steady surge in demand, so they may find it difficult to measure the ‘unearned potential income’. The same counts for achievable rough prices; without the LGD alternative on the market prices would have increased much more.

Natural producers are the only pipeline participants who are tied to natural diamonds. All others, including De Beers, are enjoying the LGD fruits.

Market share transition

For the diamond industry, the US is the primary market for diamond jewellery, which accounts for more than 50 per cent of the global market.

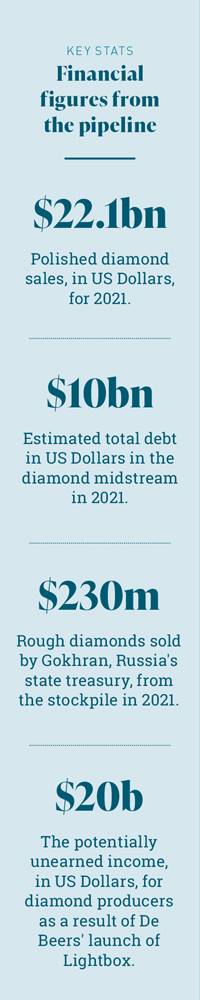

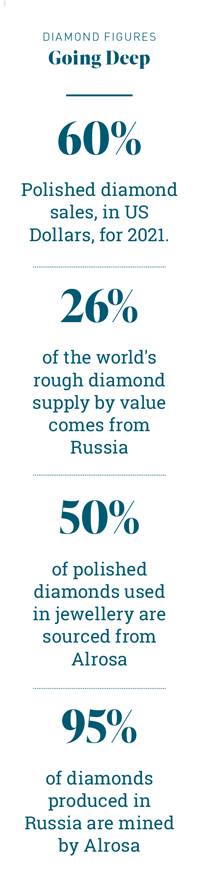

In 2021, the US market share of diamonds increased from about 54 per cent to nearly 60 per cent.

Other markets also showed a good recovery follwoing the 2020 problems and overall the retail industry achieved a growth of nearly 32 per cent, an increase of about $US85 billion. China and India were the other standout regions, with Hong Kong also recovering well.

Retailers across the world had a dream run in 2021. Not only did their sales improve, but the margins also improved across retail. While an increase in online sales meant that margins tightened, demand meant that the pricing power of the retailers increased, leading to lower discounting and effectively higher margins.

Additionally, LGD sales also increased significantly, often providing better margins than the natural product.

Due to the bull-whip (or ripple) effect in the polished diamonds pipeline, polished increased by about 55 per cent compared to 2020 to reach $US22 billion. This was despite the fact that retailers sold down from their existing inventories.

Part of this increase is attributable to the rise in prices, which averaged about 10-15 per cent for the year. However, there were specific areas that had a much more substantial price rise.

The Argyle mine, which provided about 2-3 million carats of mainly smaller and cheaper quality polished, closed in late 2020 and by 2021 all rough from the Argyle mine was exhausted. These goods were generally used in jewellery mass-produced for the US market.

The prices for these goods remained manageable for a major part of the year; however, in the last quarter, as polished stocks from Argyle rough were used up, prices moved up to levels that were about 30-40 per cent above that in the previous year.

As previously mentioned, a big chunk of the business lost due to the non-availability of the product from the Argyle mine was made up by the LGD industry, for which 2021 was even better than the previous year.

The penetration of LGD in the US market significantly increased as more stores started experimenting with maintaining LGD stock, and the LGD market suppliers have made the most of the opportunity.

Unlike previous predictions of LGD being restricted to fashion and lower-priced jewellery, bridal customers were also purchasing LGDs in significant numbers.

This implied that larger stones, including in the 2-carat plus range, remained in demand. What became apparent was that retailers were offering customers a larger LGD in the same budget, making it a value offering for customers.

At the lower end of the market, LGD jewellery could offer a better-looking product than the jewellery with polished diamonds from Argyle.

|

| Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce |

Change coming

While the market share of LGD-based jewellery is constantly increasing, a good portion of the wholesale demand for LGDs still continues to come from the introduction in new stores, rather than end-product demand.

But this will change because of the sophistication and effectiveness of LGD promotions, including the marketing spend by Lightbox.

Also, most of the suppliers of LGD jewellery come from a natural diamond background and many of the same practices such as memo offerings have started to be used in the LGD industry to push sales.

It is well known that in 2021, the diamond midstream and downstream sectors experienced what was probably one of their best years in recent memory, right up there alongside 2011.

It is well known that in 2021, the diamond midstream and downstream sectors experienced what was probably one of their best years in recent memory, right up there alongside 2011.

Actually, the same emotional love message, used for natural diamonds, is now also applied to the LGD product.

Diamond polishing has been a highly competitive business with very slim margins for most of the past decade. However, 2021 was a pleasant exception. The generally increasing polished prices meant that polishers were generally able to enjoy much larger margins.

Apart from the margins, polishers also were able to ‘right-size’ their inventory. The high demand enabled them to sell ‘non-moving’ stock, and almost all types of goods found buyers at an acceptable price.

The increased turnover and profits, along with the right-sizing of the inventory, meant that many businesses in the midstream were able to significantly reduce their leverage. The total debt in the midstream was estimated to be a little above $US10 billion.

While this was an increase over the previous year, it came on the back of significantly higher turnovers. With low-interest rates, the industry would have wanted to take on more debt – but the prevailing banking reluctance to ‘come back’ to diamonds is still very visible.

It will take time to earn back the trust and confidence that has been lost. Maybe this is for the better!

When coupled with the highly profitable year, this meant that the balance sheet of the midstream has again become extremely healthy and the businesses more bankable. In a manner, this strength allowed the companies to indulge in the speculative frenzy on rough prices in the first quarter of 2022.

Rough producers faced their own challenge in 2020, with many having to close their mines and operations either due to no sales or due to COVID-19 outbreaks. Throughout 2021, most producers sold all the rough they could produce.

A few of the larger rough producers were able to even sell down all their excess stocks, which they had built up over 2018 and 2019. Along with the sales, profitability also increased significantly for most producers, as rough prices followed polished diamond prices.

However, they didn’t see the boom they could have had.

Overall the rough producers sold about $US15.47 billion of rough or an increase of about 65 per cent in rough sales over 2020.

The rough market saw Gokhran, the Russian state treasury, sell about $US230 million of rough from their stockpile during 2021, which helped cool the market, especially for the smaller goods.

While a couple of mines in Canada faced their own issues, Gahcho Kué and Renard both had production which is skewed to the lower end of the quality spectrum.

The Renard mine had been struggling to stay afloat; however, with the increase in prices in the cheaper quality of goods, these mines and their mining companies could get a new lease of life, as the prices for cheaper diamonds are expected to remain robust.

In a nutshell, the entire pipeline had a dream year, with great sales growth and fabulous profitability for most companies across the pipeline. What is more interesting is examining some of the other factors that accounted for the industry’s success.

|

| Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce |

Pandemic a blessing in disguise

While on the one hand, the reluctance of banks to finance the industry impacted the liquidity situation (and return on capital employed decreased), the consumers and downstream in general didn’t have to extend suppliers’ credit on the same levels as in previous years.

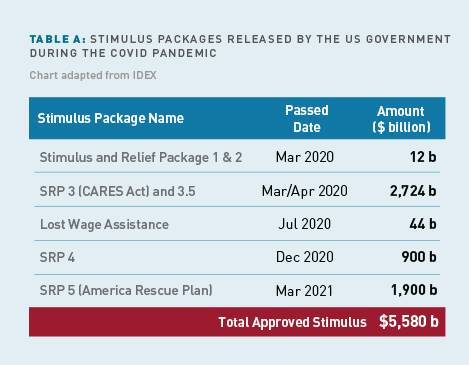

Governmental COVID-stimulus packages produced tangible benefits for the jewellery sector.

As COVID spread globally, governments reacted by imposing lockdowns and many businesses struggled to operate in those situations. While technology-based businesses could implement a work-from-home policy, service businesses could not do that and suffered greatly.

To alleviate this issue, governments offered various stimulus packages to keep businesses afloat and help them restart after the lockdowns were relaxed.

The US government offered the most generous stimulus from all governments, and over the course of two years, it amounted to nearly 25 per cent of the total GDP of the country. The stimulus was offered in various tranches and covered various different payouts and subsidies by the government.

What is equally important from an analysis perspective is the timing of the stimulus. A quick summary of the stimulus packages, which were released by the US government, is shown in the table.

|

| Above: Blush Pink Diamonds |

The dates in the table indicate when the stimulus was approved. The amounts were actually spent over a much longer period. The main points are that, in real terms more than half of the money actually reached the consumers wallets in 2021.

While many citizens did suffer in 2020 and a stimulus was necessary, the continued flow of stimulus in 2021 was the cherry on the cake, leading to a tremendous boost for the US economy.

This boost in spending was uneven and was not felt uniformly across all sectors. Certain sectors such as services, hospitality, and transportation – many of which could also be termed as essential expenses for the consumers – faced severe headwinds as the need for spending on these areas was reduced.

For example, the continued work-from-home policies for many top paying tech companies, automatically reduced fuel bills, a need for a vehicle, need for restaurants and cafes, business travel expenses, and so on.

The US consumer has not focused on savings over the past few decades but the reduced need for spending along with the stimulus meant that consumers suddenly had extra funds in their pockets.

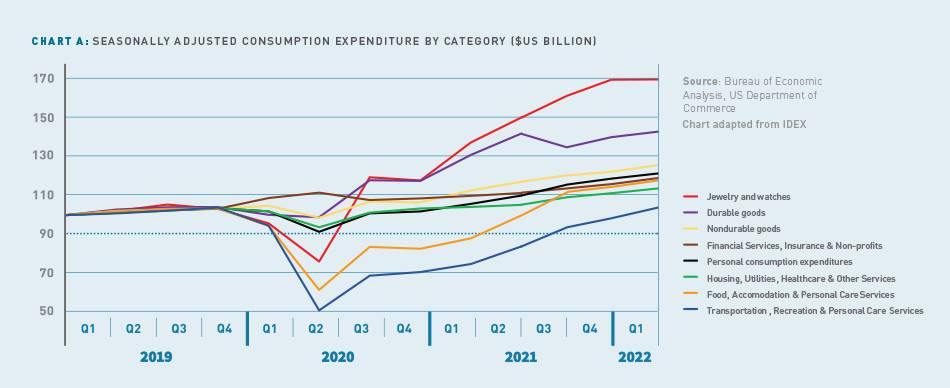

Analysis of the data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce shows the sectors that were the beneficiaries. Durable goods, which includes jewellery, seem to be the largest beneficiaries, as consumers seem to have channeled their excess disposable income into purchasing ‘hard assets’ for which they probably aspired, but did not have the income to acquire.

Up until the first quarter of 2022, overall Personal Consumption expenditure had risen by about 18 per cent compared to the first quarter of 2019, while durable goods were up 43 per cent and jewellery was up by about 70 per cent.

Clearly, the industry was better placed to garner the aspirational disposable income of consumers. Other US luxury sales also saw similar increases in the 50 per cent range, but jewellery was clearly one of the best performing sector.

Beware misleading headlines

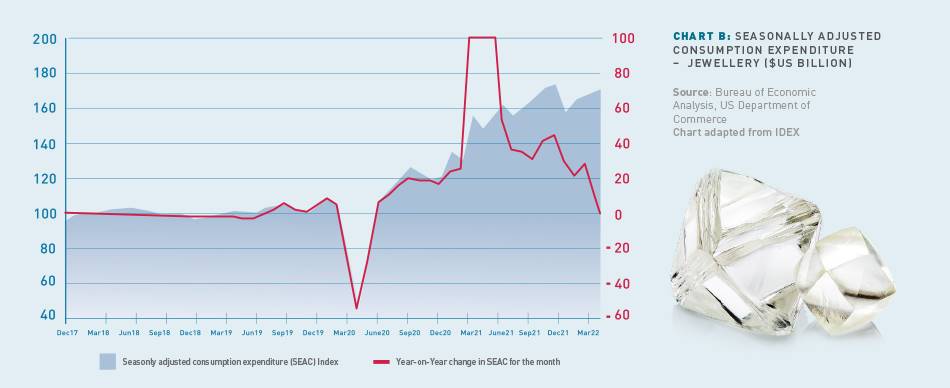

There is generally a reference to year-on-year sales for the month in news reports, and in many cases, these have made the headlines for their double-digit numbers. However, when sales have shown a large movement, it is important to have a view of both the overall value as well as a year-on-year (YoY) view of the sales.

In the first quarter of 2022 many reports showed a double-digit growth rate on a YoY basis, and traders might have been misled into believing that the industry had been growing spectacularly, possibly even fueling some of the speculation which was seen in the first two months of the year.

Looking at the complete numbers (those provided by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis are normalised on a month-to-month basis), we can see that the sales have moved in a band post-June/July of 2021. In fact, December, which is the peak season for the retail jewellery industry, had the second-lowest values in the June–December period.

Dig deeper and you’ll see a rapid increase in the January–April period of 2021, probably as consumer confidence increased along with some of the stimulus checks reaching the consumers.

This means that even when absolute values remain in the same band for Q1 2022, you will still see high double-digit YoY growth for the month, with a decreasing pattern.

The absolute numbers tell us that even if sales were to remain at current levels, you will start seeing low or negative YoY growth from June onwards. Hence it might be prudent for the industry to temper its expectations for the full year.

This stimulus money along with the quantitative easing by the central bank – and low-interest rates – unleashed funds that found their way into investments in the financial sector, which drove up asset prices across the board - housing, stock markets, cryptocurrencies, or other assets - which in turn fed into the demand through the wealth effect.

Credit card borrowing (the costliest debt) also fell significantly from the all-time high at the end of 2019 as many paid down their borrowings.

Time to pay the bills

The 2021 party, however, seems to be ending and it may be the time to pay the bills.

Most of the stimulus has been paid out and various moratoriums, which had been introduced in the US, have lapsed. The stimulus and the resulting demand had pushed up prices and inflation to levels not seen by the current generation.

The US Federal Reserve has already started to react (though it could, arguably, be late) to the higher inflation through increased interest rates, and is set to reverse its quantitative easing measures, albeit gradually. Consumer credit card debt has been creeping up and might rival the peak levels by the end of the year.

All this was expected to happen along with the tightening in the labour markets, called ‘great resignation’ by the media. The rising rates in the US have another knock-on effect, that of strengthening the dollar. In normal circumstances, a strong dollar is a negative factor for growth in the diamond industry.

The 2022 financial market situation was on the radar of most financial market observers and is not a surprise. It was expected that the diamond industry too would get back to its ’normal’ state of operations, besieged by the usual problems of low growth and insufficient profitability.

Even a best-case scenario for the diamond industry projected growth at a retail level of not more than 1-2 per cent for the year.

Even considering a flat scenario of a 0 per cent growth implied that the polished sales would drop by about $US1 billion and the rough demand would be nearly flat, as the midstream is expected to stock up again.

Looking at these projections the speculative frenzy in the markets in the first two months of 2022 was out of place and expected to correct.

All that was before the conflict in Ukraine started.

Impact of invasion

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the resultant actions taken by the Western governments could totally upend any business projections or plans which businesses might have budgeted for, especially because of the way our industry is placed, because about 26 per cent of the rough by value, and about 32 per cent by volume, was supplied by Alrosa, a company majority-owned by the Russian government.

It is increasingly clear that Russia is waging attrition warfare, a military strategy of belligerent attempts to win by wearing down the enemy to the point of collapse. This may take many months, if not years – and the hostility might still expand beyond other borders.

When the war began, the US followed by other European governments, quickly applied financial sanctions on the Russian government. They later included companies like Alrosa, which, they claimed, were financing the Russian war on Ukraine.

The first round of US sanctions prevented Alrosa from doing business in the US, something that was almost negligible and had almost no impact.

The latter round of sanctions saw Alrosa added to the Office of Foreign Assets Control Specially-Designated Nationals list.

This sanction is much more damaging because it means that no financial flows can pass through the US.

All transactions in the US dollar have to pass through banks in the US and with this inclusion, no bank would be willing to process any payments from customers to Alrosa, thereby throttling the source of income for the country.

When the sanctions were announced, the industry adopted a wait-and-watch attitude.

The speculation in the first couple of months had dulled the mid-stream’s appetite for rough and, in a way, the forced absence of rough supplies from Russia was even considered a blessing in disguise for the industry, which had started to again pile on the stock and debt.

Companies were hoping for a quick resolution to the conflict and wishing that things would go back to normal. However, hope is not a strategy. As the conflict drags on, the solution seems to be squarely in the realm of politics.

Unfortunately, the fate of the conflict will seemingly be determined by people who have very little to lose, which would mean that a resolution and the eventual lifting of financial sanctions seem to now be a distant possibility.

Living with sanctions

The world had been effectively uni-polar – with only one dominant nation – for more than 30 years. Nations across the world are now aware of the damages that financial sanctions can cause and now understand the will of the US

to weaponise them.

As we go forward, the world will start becoming multi-polar – driven by multiple strong and competing nations – once again with the trade of different countries and blocs being primarily restricted to each bloc separately.

In the past decade, financial sanctions have increasingly become the US weapon of choice, given its dominant position in the global financial system. Raghuram Rajan, a leading economist, termed financial sanctions as ‘weapons of mass destruction’ due to their blunt nature in trying to effect change.

While sanctions might be inhibitors and have a preventive impact, they have not shown any success in providing immediate solutions once a conflict has started. Countries and citizens may go well beyond their perceived capacities to face sanctions when they feel that they are being unjustly treated.

Without going into which side is justified in their view, sanctions can be considered unilateral and gaining their power from the dollar being the primary global currency.

The manner in which governments have gone about applying sanctions also reeks of hypocrisy. Some countries give waivers to sanctions, which are inconvenient, or can cause significant upheaval.

For example, waivers have been given on products such as oil, natural gas, uranium and titanium where Russia is a major supplier for the nations applying the sanctions. Developing nations have started complaining about the impact of the sanctions on countries that are, effectively, innocent bystanders.

Another notable aspect of this Russia-Ukraine war was how quickly businesses, including jewellery retailers and brands, decided that they would not by Russian-origin diamonds. Many have a constant customer interface and probably reacted in this fashion due to their individual political, social or moral compulsions.

These ‘business sanctions’ have further affected the pitch for the industry. Alrosa, in fact, had been at the forefront of promoting industry self-regulation initiatives such as the Responsible Jewellery Council, and the updated World Diamond Council System of Warranties. It is ironic that now these very same chain-of-warranty mechanisms are being used by the industry to exclude Alrosa.

In future, other countries and companies might not be willing to join such cooperative mechanisms, as no country or company can confidently say that it could not be next to face sanctions. Irrespective of how long the sanctions last, it is clear that the industry will find it extremely difficult to come to a common ground, or agree on, any self-regulation mechanism in the future.

New environment

It is clear that for the diamond industry, sanctions are here to stay and the industry needs to be ready for the long haul, and choose which side to take. The sanctions will probably continue even after the conflict stops.

One of the primary strengths of the industry is its resilience and the adaptability of its companies, as it has proven again and again over the decades. Reports indicate that Russian rough has already started finding its way to the market.

In the event that the industry transitions into a multi-polar environment, companies clearly need to take sides, having to scale down their business in order for them to continue being compliant.

With the current regulations in place, the industry is likely to be split down the middle, with some companies abiding by the sanctions and other companies dealing in Russian diamonds, but not supplying them to the developed world.

We are confident even in a multi-polar world that the industry will continue to adapt and thrive as it has done in the past.

Unfortunately sanctions tend to provide the greatest reward to companies that dodge sanctions, at the cost of the responsible companies leading to a fall in the industry compliance standards.

Matter of cost

The US has been trying for more than a decade to get the diamond industry to segregate its inventories. This was initially proposed for diamonds from Zimbabwe. Various chain-of-custody initiatives were proposed by the US government agencies to prevent Zimbabwean diamonds being sold in the US. These efforts met with at best partial success. Some diamonds from Zimbabwe were easily identifiable and the volume of supply from the country was limited.

The authors wrote extensively at that point about the segregation of diamonds. The views expressed remain the same even after 10 years, namely:

• Segregation of larger stones (>0.20 carats), which are generally polished individually, can be done managed by the industry.

• The challenge is in the smaller diamonds, which are traded and sold in parcels with parcels being mixed multiple times.

• It is still feasible to segregate diamonds, however there is a significant cost, which would need to be borne by the midstream for maintaining the diamonds separately.

• The authors questioned the ability of the midstream to bear those costs, which were more than $US1 billion on an annual basis. Costs had to be passed on to the consumer or borne by the mines.

• It could mean an increase in polished prices of more than 10 per cent in the concerned category of goods.

Our observations in the matter still hold. However with the current emotional support for Ukraine and the general inflationary environment in many developed nations, it might be easier to pass on these costs to the consumers. It is to be seen whether the resolve will remain once the consumer attention moves on to other issues.

Availability

Aside from the cost perspective, the removal of supplies from Alrosa could cause severe availability problems for certain kinds of companies. As mentioned, Alrosa diamonds represent about 26 per cent of diamonds by value and about 32 per cent by volume. Clearly, their diamonds are smaller with a lower average cost as compared to the market.

The impact of the Alrosa sanctions across different categories of diamonds is different, given the production mix of their mines.

Polished which is produced from Alrosa rough, has a much higher share in diamond categories that are used by luxury, lifestyle, or high-fashion brands. In many of these categories, Alrosa accounts for over 50 per cent of the polished diamonds supplied.

Companies in these sectors could face serious issues in obtaining supplies, especially in the latter half of 2022. It is indeed ironic, that many of these luxury brands were some of the first to stop using Russian-origin diamonds.

Crossing the Rubicon

Luxury brands take great care in cultivating their image over decades and most big brands have stayed away from using lab-grown diamonds in their jewellery or watches. Going forward, with the Alrosa supplies not useable, they could face a supply shock, as there might not be enough diamonds to meet their requirements.

The question remains whether they will cross the Rubicon and decide to use LGD in their luxury products and whether their consumers will accept those products and the ‘advertising spin’ their marketing teams will give for that decision.

The only segment that would be laughing all the way to the bank would be the LGD industry.

Companies have had a phenomenal year, and supply shortages can lead to new business opportunities for LGD jewellery companies, as retailers try to fill their shelves for the upcoming Christmas and holiday season.

LGD producers also have not scaled up their capacities to a stage where they can replace Alrosa production. For a change, they might see price increases in the second half of 2022.

More than the incremental business, the shortages will open new opportunities for LGD suppliers, as retailers who would have otherwise not considered selling LGD jewellery are forced to go ahead and offer the product. No wonder the current market conditions might seem like heaven for the LGD industry, while diamond-producing countries continue to lick their wounds.

This is an edited version of an article that was first published by IDEX Online in August 2021, and is reproduced with permission. Visit idexonline.com.

READ emAG