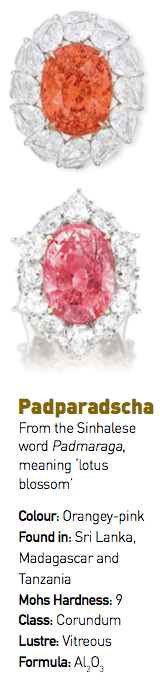

The pretty Padparadscha gemstone was first discovered in Sri Lanka and named after the Sinhalese word “Padmaraga”, meaning lotus blossom – a species of flower that was originally a soft pastel orangey-pink.

The pretty Padparadscha gemstone was first discovered in Sri Lanka and named after the Sinhalese word “Padmaraga”, meaning lotus blossom – a species of flower that was originally a soft pastel orangey-pink.

Later sources of Padparadscha sapphire include Madagascar and Tanzania; however, purists believe the “true” material to be of Sri Lankan origin.

Coloured by the trace elements chromium and iron, Padparadscha sapphire possesses various attractive attributes besides its obvious beauty.

It has a high hardness – nine on Mohs’ scale – and excellent durability, making it a popular choice for everyday wear and more recently as an engagement ring gemstone. Additionally, it can withstand the heat generated by standard jewellery repair processes.

In 2007, the Laboratory Manual Harmonisation Committee (LMHC), of whom the Gemmological Association of Australia (GAA) is an affiliate, standardised the nomenclature used to describe Padparadscha sapphire.

This was later updated in 2011 as: “Padparadscha sapphire is a variety of corundum from any geographical origin whose colour is a subtle mixture of pinkish orange to orangey-pink with pastel tones and low to medium saturations when viewed in standard daylight.”

The description excludes modifiers other than pink or orange. In addition, the overall colour must be free of major, uneven colour distribution when viewed with the unaided eye and the table up to +/- 30 degrees, and should not have any yellow or orange epigenetic material affecting the overall colour of the stone.

While most dealers and collectors agree this gemstone should display a blend of pink and orange, it’s interesting to note that the exact ratio, tone and saturation are open to interpretation, as are the presence of secondary tones such as brown, yellow and red.

The LMHC Padparadscha definition excludes any treatment, except for traditional heat, which is used to dissolve ‘silk’ and improve clarity.

According to CIBJO, the World Jewellery Confederation, only untreated and heat- treated Padparadscha sapphire qualify for the prestigious title of Padparadscha.

In the early 2000s, bulk beryllium diffusion- treated sapphire flooded the market.

This treatment involved coating sapphires with beryllium oxide and other compounds and subjecting them to very high temperatures for several days, causing the diffusion of colour through most or all of the stone and creating a Padparadscha- like appearance.

Fortunately this treatment can now be detected through a combination of standard and advanced gemmological techniques.

Other treatments used to create a Padparadscha-like appearance include coating, dying, irradiation and glass-filling.

Gemstones such as topaz, spinel and garnet may be sold as Padparadscha imitations, and copycats like synthetic orange-pink sapphires are plentiful.

Finding a true Padparadscha sapphire can be challenging due to its limited availability. The key is to establish a good relationship with a competent gemmologist, valuer or jeweller and ask for a coloured gemstone report from a reputable laboratory.