After a long-dormant period in the jewellery market, pearls enjoyed something of a renaissance in the 2010s, returning to fashion catwalks and jewellery houses in new and exciting designs.

With a wide variety of cultured pearls on the market – and their comparatively affordable price point – consumers responded with enthusiasm.

The renewed passion for pearls was reflected in record-breaking auction prices. A large natural pearl pendant once belonging to French queen Marie Antoinette sold for $US36.1 million ($AU53.8 milion) in 2018, more than ten times its estimate; the La Peregrina pearl necklace, previously owned by actress Elizabeth Taylor, was auctioned for $US11 million ($AU16.4 million) in 2011.

The renewed passion for pearls was reflected in record-breaking auction prices. A large natural pearl pendant once belonging to French queen Marie Antoinette sold for $US36.1 million ($AU53.8 milion) in 2018, more than ten times its estimate; the La Peregrina pearl necklace, previously owned by actress Elizabeth Taylor, was auctioned for $US11 million ($AU16.4 million) in 2011.

Since then, the sector has continued to evolve, with ever more creative settings and combinations of pearls with other gemstones and metals.

To cope with the increased demand, pearling operations have expanded to more than 30 countries.

More than 98 per cent of the pearls produced worldwide are freshwater cultured pearls grown in China. Meanwhile, Japan, French Polynesia, Indonesia, and Australia are leading producers of saltwater pearls, including Akoya, Tahitian, and South Sea pearls.

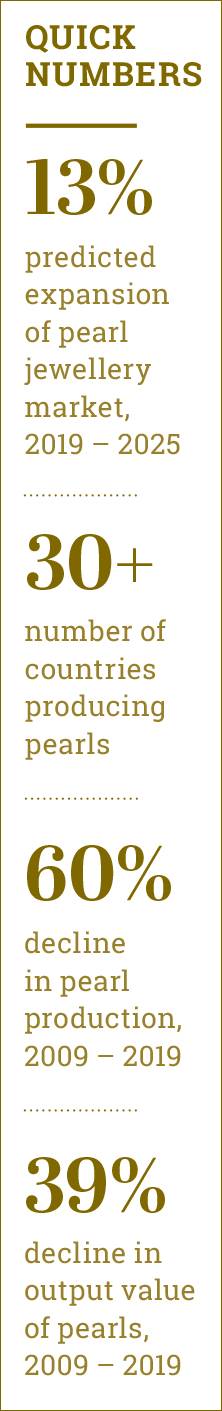

In its December report, US research firm Arizton Advisory & Intelligence projected that the global pearl jewellery market would expand by 13 per cent between 2019 and 2025.

However, the pearl sector is also facing serious challenges, including declining output and quality. According to research from the South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute (SCSFRI) and Australia’s University of the Sunshine Coast (USC), published in 2019, global pearl production fell by 60 per cent and output value by 39 per cent over the past decade.

The sensitivity of pearl molluscs to environmental change, pollution, and natural disasters – as well as the technical precision required for sustainable pearl husbandry – place unique constraints on this sector of the jewellery industry.

As a result, jewellers are turning to a variety of countries for their pearls, exploring more local options, or opting for sophisticated pearl simulants to satisfy customers’ desire for the gem’s uniquely captivating sheen.

Perfectly Imperfect

One of the dominant trends of the past two years is the rise of baroque – irregular shaped – pearls, and demand shows no sign of slowing down in 2020.

Ikecho Australia stocks a wide variety of Akoya, Mabe, freshwater, Australian South Sea and Tahitian pearl jewellery, and founder Erica Miller says freshwater baroque style pearls have been the most commonly purchased shape over the past 12 months.

Far from the uniform symmetry of a classic round pearl, baroques reflect the organic and unpredictable nature of pearl formation – and allow jewellers abundant opportunities for creative design.

They have been seen on the recent catwalks of fashion houses like Alexander McQueen and Dolce & Gabbana.

“In the past 12 months we have seen trends towards the baroque shaped pearls, with the irregularity and uniqueness of each baroque pearl appealing to customers more recently,” says Justin Linney, creative director at Linneys Jewellery in Perth.

Rachael Abbott, marketing director at Timesupply – which distributes Coeur de Lion, Qudo and Dansk – has also noticed the baroque trend in the fashion jewellery category.

“The Dansk Baroque pearl collection has proven very popular, adding texture and contrast to this already very unique, edgy range inspired by the raw structure of nature.”

This trend is in line with the Gen Z and Millennial consumers’ desire for authenticity and personalisation; instead of a perfectly matched string of pearls, consumers are embracing mismatched earrings and multicolour strand necklaces.

“Multi-coloured strands are an easy-to-wear option because one strand goes with a lot of colours in terms of clothing, and can work both in the evening and daytime,” says June Mann, director of Pearl Specialists, which supplies Japanese Akoya, South Sea and Tahitian pearls.

“Pearls with a strong design element – not just plain strands but mix of different sizes, or pieces that combine pearls with different gemstones – have also become more popular.”

Meanwhile, Linney says the fashion jewellery sector’s trend for faux pearl hair clips and pearl-embellished clothing has “translated through to fine jewellery”, with Linneys Jewellery receiving more enquiries into brooches and pins.

|  |  |

| Above: Annoushka | Above: Autore | Above: Ikecho Australia |

|  |  |

| Above: Paspaley | Above: Linneys | Above: Timesupply |

Colour and Lustre

However, baroques are not the only trend shaping today’s pearl market. There is still room for the classics, with Miller noting that large freshwater pearls – measuring more than 12mm – have become popular due to their ability to mimic the expensive look of South Sea pearls.

Australian South Sea pearls are considered to be the highest quality and most expensive in the world. Grown in Pinctada maxima giant oysters off the coast of Western Australia in saltwater beds, these pearls are prized for their large size and enticing lustre, which is likened to a soft glow rather than the more mirror-like sheen of freshwater pearls.

“Our collection is predominantly the Australian South Sea pearls as we are renowned for creating unique jewellery with these pearls – although we also love working with golden South Sea and black Tahitian pearls,” Linney says.

Indeed, the wider market is embracing golden South Sea pearls, largely sourced from the Philippines and Indonesia. Jewelmer, a company specialising exclusively in golden South Sea pearls and pearl jewellery, opened its first boutique outside the Philippines, in Palm Beach, Florida, last year.

In the CIBJO Pearl Commission’s annual report, published in November last year, Jewelmer noted that Myanmar (Burma) is a burgeoning competitor in the golden South Sea pearl market, though quality and volume remain unstable.

Further along the colour spectrum, Mann says “darker natural blue Akoya have become popular in the 8mm and above sizes, both round and baroque, and peacock-coloured Tahitian pearls remain popular, particularly larger sizes of 12mm and above.”

A significant benefit of pearls is their broad colour spectrum, which makes these gems adaptable to different jewellery designs and finishes.

In addition to classic white Australian South Sea pearls and Japanese Akoya pearls, and black Tahitian pearls, Ikecho stocks freshwater Edison pearls. These nucleated pearls are grown in the Hyriopsis cumingii, or triangle mussel, and display natural colours of purple, peach, pink, and gold, as well as white and grey. Ikecho also stocks multicolour freshwater Keshi pearl bracelets and multicolour Tahitian pearl necklaces.

Faux pearls such as Swarovski crystal pearls are another option for jewellers looking to offer a broader range of colours and cater to the fashion jewellery market. They have the added benefit of being more hardwearing than natural pearls, which are graded at 2.5 on Mohs’ scale.

“Pearl-style jewellery continues to be popular, with unique uses of complementary materials such as cut glass and Swarovski crystals in rose gold and champagne tones creating a beautiful an elegant style alongside pearl textures,” Abbott explains.

She adds, “Swarovski crystal pearls continue to be very popular in the Qudo Interchangeable range, where a variety of styles and colours adorn rings, necklaces, earrings and bracelets.”

PEARL COLOUR CHART

A Rainbow of Colours |

Like diamonds, untreated pearls can be found in a wide variety of colours. The colour of a pearl is determined by the type of mollusc it originates from, the thickness of its nacre, and miscroscopic pigments in its conchiolin – the organic ‘glue’ within the nacre. There are three components when observing pearl colour: body colour, overtone, and orient. The body colour is the dominant hue of the pearl, while the overtone refers to the ‘translucent’ or reflective colours of the pearl and the orient is the rainbow-like iridescence of the pearl. |

| WHITE

Both saltwater and freshwater molluscs can produce the classic white pearl, but Australian South Sea pearls from the silver-lipped Pinctada maxima are the most sought after. |

| BLACK

The black-lipped oysters of the South Pacific, Pinctada margaritifera, produce natural black pearls, often referred to as Tahitian pearl. Rainbow-lipped oysters – Pteria sterna, found in Mexico – also produce natural black pearls. |

| LAVENDER

Freshwater pearls from the Hyriopsis cumingii mussels occur in shades from pale lilac to deep violet. They are often grown in China. |

| PINK

Freshwater pearls – those grown in mussels like Hyriopsis cumingii and Cristaria plicata – can be naturally pink. They are commonly farmed in China and Japan. |

| GOLD

Gold-lipped Pinctada maxima oysters produce golden South Sea pearls. These pearls can range from soft champagne to deep gold, with more saturated colour commanding higher prices. They are found in the Philippines, Indonesia, Australia and Myanmar (Burma). |

| GREEN

On the east coast of Australia, Pinctada fucata are cultured to produce Akoya pearls with a variety of natural hues, including a unique silver-green. |

Unusual appeal

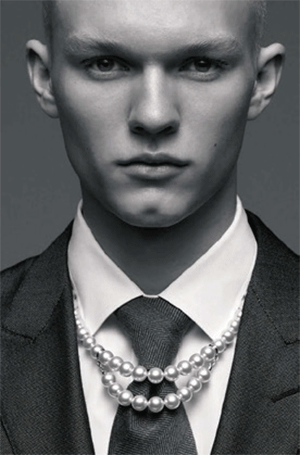

Perhaps the most unusual development in the sector is the increased number of men embracing pearl jewellery.

Pearls have long been associated with femininity, and traditionally, men have preferred more robust gemstone or metal pieces that require less care.

Yet, men’s pearl jewellery – particularly necklaces, but also earrings and brooches – have recently graced the menswear collections of designers like Gucci and Dior. Meanwhile, Japanese pearl producer Mikimoto recently announced a jewellery collection designed with fashion brand Commes des Garçons.

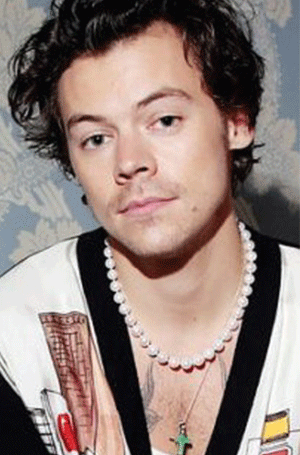

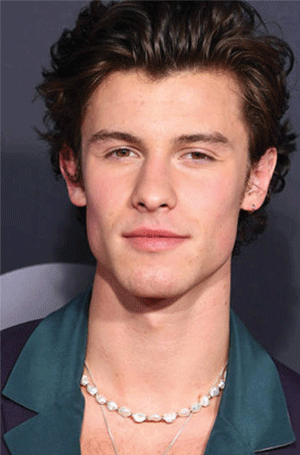

Lead by celebrities including rapper A$AP Rocky, singers Harry Styles and Shawn Mendes, and actors Ezra Miller and Kris Wu, the men’s pearl trend is beginning to gain traction on the red carpet as well as the catwalk.

Some jewellers have already incorporated pearls into their men’s collections – albeit in a more subtle and conservative way, to appeal to the tastes of Australian customers.

At Linneys Jewellery, Tahitian pearls are fashioned into neoprene cuffs, nestled alongside 18-carat rose gold, tantalum metal, and flush-set white diamonds.

“We notice that men are initially given jewellery as a gift, then once they start wearing it and enjoying it, they will feel confident to buy it for themselves,” Linney says. “The black Tahitian pearls provide a stunning range of colours – from peacock green to grey and purple hues – that give a masculine look to the men’s jewellery. Pearls are also more hard-wearing than people assume,” he adds.

Indeed, while pearls have a reputation for fragility, treatments such as bleaching are often responsible for cracks and splits in the nacre. Untreated pearls may be selected to avoid this problem.

Additionally, men’s pearl cuffs are also unlikely to be degraded by hairspray, perfume and cosmetics, which can occur with women’s jewellery.

To ensure pearl pieces last, Mann recommends jewellery retailers offer all customers advice on pearl care, including cleaning and storage. “Proper care makes a lot of difference how long they will keep their beauty,” she says.

2020 TrenD

Men in Pearls |

|  |  |

Mikimoto x Commes De Garçons

jewellery collection 2020 | Harry Styles has been spotted in pearls multiple times in the past year | Shawn Mendes wore pearls at the MTV VMAs and the 2020 Grammys |

Factors impacting the pearl supply

While the pearl market remains robust, there are challenges in sourcing both locally and internationally.

“Because pearls are a natural organic gemstone, they are not always available, depending on the time of year,” Miller explains. “At harvest time, sometimes we can’t supply particular shapes and colours. Our customers understand, and we will offer them an alternative to suit their needs.”

As an organic gemstone from the marine environment, the pearl supply is also particularly susceptible to changes to ecosystems and farming practices.

The SCSFRI and USC research noted that “urbanisation and industrialisation in traditional pearl farming areas, and stressed and impoverished coastal environments have led to some serious problems and big challenges for sustainable development of the pearl aquaculture industry.”

These factors have reduced oyster supply, growth rates, survival, and pearl yield and quality in some countries.

Perhaps the most well known example is the proliferation of Akoya viral disease amongst the Japanese oyster population in 1996. An influx of pollution caused widespread immunological collapse among Akoya pearl-producing Pinctada fucata, drastically reducing pearl yield and quality.

In 2019, Japanese authorities confirmed the sudden death of 20 million Akoya pearl oysters, reducing stock by 70 per cent in some areas.

According to Takeshi Miura, a professor at Ehime University Faculty of Agriculture, it was the first mass die-off since 1996.

Miura attributed the deaths to multiple factors, including underfeeding and overcrowding, and the effects are expected to be felt in 2021, when the oysters would have been harvested.

Meanwhile, Chinese pearl producers have faced several rounds of government bans and closures over the past four years for breaches of water quality standards, introduced in 2015.

In order to increase production, farms also began overstocking and reducing the production cycle – harvesting earlier than usual – resulting in pearls with thin nacre.

As a result, the Chinese pearl industry has consolidated into fewer producing farms, and increasingly relied on post-harvest treatments such as bleaching and maeshori.

A technique developed in Japan, maeshori is used to improve lustre, one of the most critical pearl grading elements alongside size, shape, colour and surface quality. It also assists in the bleaching process, known as hyohaku.

However, maeshori leaves the nacre more brittle, and over-treatment can cause pearls to become ‘chalky’.

Recent reports suggest maeshori is now extremely widespread in the Chinese and Japanese freshwater pearl industries – to the extent that many do not consider it a ‘treatment’, but rather a normal component of pearl processing.

Mann, who sources Akoya pearls in Japan, explains, “Not everyone follows the same process, but maeshori is the standard practice on Akoya pearls in some form or another, except for genuine namadama – completely untreated/unprocessed pearls.

“The details of the process can vary. Maeshori usually involves soaking the pearls in an alcohol solution to make the bleaching process more effective and to remove some of the yellow hue.”

Mann considers alcohol-soaking maeshori to be “more of a mild pre-processing than a treatment” as it does not substantially change the pearls.

Japan remains the largest Akoya pearl producer in the world, with an industry valued at $US127 million ($AU189 million) per year.

According the CIBJO Pearl Commission report, a new dedicated Pearl Council has been established in Japan with a mandate that includes promoting the sustainable production of oysters and pearls, improvement of productivity and quality of the pearls, and conservation of the pearl farm environment.

Meanwhile, Katherine Kovacs, director K&K Export Import, says pearl stocks can be threatened by factors other than unsustainable farming practices or over-treatment. “Natural disasters can have a significant impact on pearl production as they can drastically alter the marine environment, as well as destroy the infrastructure of pearl farms,” she explains.

Earthquakes are frequent in Indonesia, which is the world’s largest producer of South Sea pearls by volume.

According to the CIBJO Pearl Commission report, “greater fluctuations in water temperature, ocean acidification, and the changing of the plankton profile” as a result of climate change will also limit pearl volumes from the Philippines in the next year.

|

| Above: L to R: Autore, Paspaley, Kailis, Ikecho Australia |

Supply chain integrity

Alongside sustainability, provenance has become a focus of the broader jewellery industry. In the past 12 months, CIBJO released its first Responsible Sourcing Blue Book and its ‘Do’s And Don’ts’ guide to ethical and responsible gem handling.

Speaking to Jeweller last year, Russell Shor, senior industry analyst Gemological Institute of America, said, “Along with sustainability, consumers also want to know where their gems, and even their gold, come from.”

It’s a consumer trend noted by Linney, who adds that a pearl’s origin can form a unique selling point for jewellers: “Our customers are certainly interested to know where the pearls in their jewellery come from in regards to being ethically sourced, but also because it is part of the story as to how they were formed and the lure of the pearl,” he explains.

However, there has been difficulty applying traceability intiatives to the global pearl industry. While the diamond industry has pursued blockchain tracking through laser inscription, the technique is not applied to pearls as they are not routinely certified.

Additionally, scientific analysis of pearls cannot determine a pearl’s country of origin. However, it is not impossible to ensure traceability in the pearl supply chain.

As of 2017, all commercial wild-catch oysters in Australia have been independently certified against the standards of the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), an international non-profit organisation that promotes sustainable fishing.

A spokesperson for the Marine Stewardship Council told Jeweller, “The MSC sustainability standards comprise not only how the oysters are caught in the wild, but also the journey through the supply chain from the ocean to the consumer.

“To meet our Chain of Custody Standard, each part of the supply chain is audited. In order to achieve and maintain certification, companies undergo regular scheduled and unannounced surveillance audits from an independent accreditation body.”

The MSC certification applies to all wild-caught Australian South Sea pearl oysters, such as those harvested by Paspaley, Australia’s oldest and largest pearling business.

Ultimately, while the pearl sector may face unique difficulties in the short- and long-term, governments and businesses are responding to ensure the future remains bright for this uniquely beautiful gem.

WHAT IS MAESHORI?

The term maeshori translates to ‘before treatment’ in Japanese. While techniques vary, it usually involves soaking pearls in hydrogen peroxide and/or methyl alcohol, mineral salts and ammonia, or alternately heating and chemically treating the gems in order to reduce the space between the nacre platelets.

| | Above: Pearl Specialists |

For this reason, it has been described as a pearl ‘facelift’ as it ‘tightens’ the nacre and thereby improves lustre. June Mann, director Pearl Specialists, sources Akoya pearls in Japan that have undergone maeshori. She explains: “Generally, pearls that have gone through just maeshori – and also generally hyohaku (bleaching) – are still sold as ‘natural’, and certainly as muchoshoku, meaning not colour-enhanced. In fact, muchoshoku includes those pearls that have gone through both maeshori and hyohaku.” Mann considers the alcohol-soaking form of maeshori to be a mild form of pearl processing: “It is less of a treatment than the polishing that is often performed on Akoya, and certainly much less of a treatment than bleaching or colour enhancement,” she adds. Australian Akoya pearls – which are grown in limited numbers on the mid-north coast of New South Wales – do not undergo maeshori. They display a high-quality lustre due to thicker nacre, which is achieved through longer growth times for the oysters. |

READ EMAG