Antique and vintage jewellery has always stood apart. In a world seemingly obsessed with the latest innovations and cutting-edge technologies, these pieces – meticulously crafted by hand, built to last, often one-of-a-kind – offer a compelling contrast that appeals to a small, yet passionate subset of consumers.

Antique and vintage jewellery has always stood apart. In a world seemingly obsessed with the latest innovations and cutting-edge technologies, these pieces – meticulously crafted by hand, built to last, often one-of-a-kind – offer a compelling contrast that appeals to a small, yet passionate subset of consumers.

It is important to note that in jewellery terms, ‘antique’ refers to jewellery that is more than 100 years old. ‘Vintage’ is generally used to describe pieces made 50–99 years in the past.

“There has always been a following for antique and vintage jewellery,” confirms Kathryn Wyatt, owner of Imogene Antique & Contemporary Jewellery in Melbourne and publicity and marketing officer at the Gemmological Association of Australia (GAA).

Far from being the province of older consumers motivated by nostalgia, the antique and vintage category has a broad following.

Justin McCabe, sales director at Gerard McCabe Jewellers in Adelaide – which stocks vintage and antique jewellery alongside modern collections – says, “We sell to newly- engaged couples buying vintage rings, younger people in their late teens and early twenties, and people in their eighties and nineties.

“There’s certainly a wide range, and we have even seen a few younger gentlemen buying pocket watches.”

Wyatt tells Jeweller, “Certainly, there are younger people under 30 who are looking to invest in jewellery, and older people too. The people who buy pieces from me say, ‘I want something unique’; they don’t want the mass-produced jewellery that all their friends have. They want something different.”

Indeed, it is that ‘one-off’ quality that draws Gerard McCabe customers toward the antique section.

“The pieces themselves have a lot of character,” says Justin McCabe. “There is a distinction between them and modern jewellery. Many of our modern designs come in suites and collections, and they are often more streamlined and stackable.

“Whereas the pieces of the past are just that one piece, with a lot of creativity and workmanship, and if you can find something special that’s in great condition and speaks a story to you, it’s like finding treasure.”

Damien Kalmar, of Kalmar Antiques in Sydney – which deals in antique and vintage jewellery and pocket watches – also observes that antiques cut across age demographics, appealing equally to both men and women.

He notes the “uniqueness” and “romantic feel” of older pieces, particularly those from the Victorian era.

Caroline Tickner, of auction house Leonard Joel, points to the quality of antique jewellery as a major selling point.

“Valuable antique jewellery is fundamentally based on beauty, craftsmanship and rarity,” she explains. “Some of the techniques undertaken by jewellers in the 19th Century verge on being lost artisan skills.

“Workmanship such as enamelling, pietra dura, and cannetille are highly specialised forms of decoration that few can replicate.”

Marlene Crowther, of Keshett in Melbourne, adds, “Antique jewellery combines so many appealing elements it would be harder to find reasons why it would not appeal to consumers than why it does!”

“The style of different periods is captured in precious metals and gems. People who are likely to buy antique jewellery are those with imagination – those who can allow themselves to be transported to another time when they contemplate a beautiful period piece,” she explains.

Crowther believes antique jewellery lovers “feel privileged to have custody of a fine antique piece of jewellery and can imagine those who owned it before and those who will own it next,” adding, “Antique jewellery is a celebration of fearlessness, creativity, and beauty stretching before and beyond us.”

Aside from romance, craftsmanship, and history, Wyatt also points to the environmentally-conscious nature of the category:“My customers like the idea of buying something that is ‘recycled’. Antiques are sustainable; they already made their tiny ‘carbon footprint’ years ago, and if they’ve lasted 100 years, they are usually going to last a fair bit longer!”

Sales patterns

McCabe estimates antique and vintage jewellery now comprises 15–18 per cent of sales across Gerard McCabe’s two stores, with seasonal fluctuations.

“Christmas can prove extremely strong for our antique and vintage business, and some months it can be more than 40 per cent of a store’s turnover,” he explains.

While the COVID-19 pandemic limited the number of international customers in the stores, McCabe noted that the mid- to high-end market remained “alive and well”, driven by local shoppers who would ordinarily be travelling overseas.

Rikki McAndrew, director of Melbourne’s McAndrew Jewellery and a registered valuer with the National Council of Jewellery Valuers (NCJV), has also observed strong higher-end sales, though the lower end of the market has seen increased competition from designer branded jewellery, particularly sterling silver collections.

Like Wyatt and McCabe, he notes that the types of consumers who buy antique jewellery are not constrained to a particular age group, but rather are people who “don’t follow trends but prefer to have some individuality, and appreciate the history and workmanship involved in antique jewellery”.

He explains, “Antique jewellery sells on its own merits; it doesn’t have the benefit of marketing campaigns or promotions, whereas fashion jewellery and branded jewellery often needs constant marketing to stay relevant to consumers.”

In addition to the ever-present competition from contemporary jewellery, a number of other challenges remain for antique jewellery retailers, including reliable sourcing, developing a comprehensive pricing system, and adapting to e-commerce.

Market trends

Among antique and vintage jewellery retailers, one era stands head and shoulders above the rest in terms of consumer demand: Art Deco.

Among antique and vintage jewellery retailers, one era stands head and shoulders above the rest in terms of consumer demand: Art Deco.

“For the past 30 or 40 years of my doing business, Art Deco has always been popular and it is probably the most popular,” Wyatt says, adding, “Technically, it’s not antique – or only just – as the Art Deco period is defined as 1920–1935.”

“In recent months there has been a resurgence of yellow gold, Victorian pieces too,” she adds.

Crowther has observed similar trends in engagement rings: “In the last decade there has been a noticeable shift in the engagement ring market to the geometric designs of the

Art Deco period, with symmetrical lines, unobtrusive white metals, and diamonds subtly accented by calibre-cut coloured gemstones appealing to young buyers,” she says.

Tickner concurs: “Art Deco jewellery is always popular, with its fabulous streamlined form and simplicity,” adding, “Platinum is always desirable as well and stands the test of time, and ‘significant’ antique pieces are most in demand in recent times – whether it is a large European cut or old mine-cut solitaire diamond ring, a fabulous pair of Georgian foil-back girandole earrings, or a high-Victorian heavy gold brooch.”

McCabe has also observed a resurgence in demand for “statement pieces” in the past 12 months, in particular rings followed by necklaces and bangles with “a big splash of colour”.

And while he believes Art Deco remains “everyone’s favourite”, purchasing patterns at Gerard McCabe have tended more toward the late-Victorian period, with yellow gold and brooches “making a comeback”.

For McAndrew, “the classic Art Deco design is always in demand”, with Art Nouveau – traditionally dated between 1890 and 1910 – also prized by collectors.

“Early Australian ‘goldfields’ jewellery is rare and also always in high demand; some pieces have no stamp and others will have an Australian maker’s mark, some being rarer than others,” he says.

“Trends and fashions come and go – nowadays most likely according to the latest marketing campaign, influencer or Instagram sensation, so there is no reason that certain styles of antique jewellery won’t be the next ‘must-have’.”

Indeed, Crowther observes that ‘fashions’ are often fuelled by celebrities, such as the engagement rings of actress Scarlett Johansson and British socialite Pippa Middleton.

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder – a beholder usually led by fashion and contemporary attitude!” she remarks.

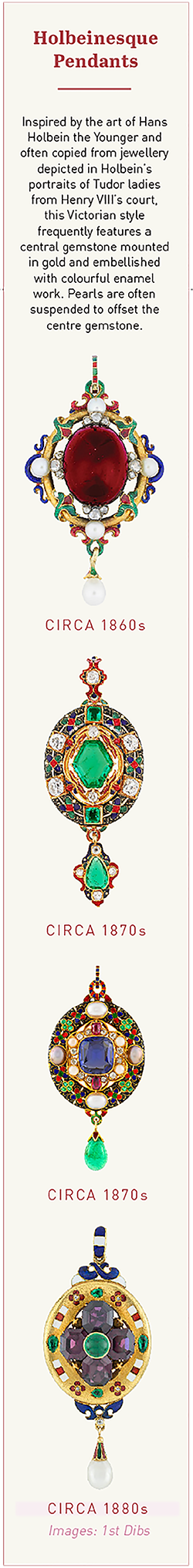

“Many customers are happy to have items made in the style of certain periods without having a need for authentic antique pieces,” she adds. “This is not a new development and reproductions have always had a significant market share.”

Indeed, the prevalence of reproductions – made throughout the 20th Century and in the modern day – frequently prove a thorn in the side of antique and vintage jewellery retailers.

The genuine article

Perhaps the most pressing challenge to stocking antique and vintage jewellery is sourcing authentic pieces.

“It has become harder to find original and genuine antique pieces as they do wear out and become damaged. Repairs do impact their originality and value and there are plenty of cast reproductions in the marketplace,” Tickner observes.

Wyatt notes, “If you think about it, things that are 100 years old – there’s not a lot of them [left],” notes Wyatt. “Even if we go back to the Art Deco period, there wasn’t actually a lot of jewellery produced at that time, particularly in Australia, because of the Depression. So there’s not a lot around, full stop – and if there’s not a lot around, people reproduce it to cater to that demand.

“We tend to see a lot of Art Deco reproductions, because that is the largest market, and Victorian reproductions too. Pieces are often made in Bangkok and Argentina.”

Wyatt notes that since reproductions have occurred throughout the 20th Century, authentication is particularly difficult given older reproduced pieces now show wear.

“English late-Victorian earrings were reproduced in Spain in 15-carat gold and sold right across the world, so now when you see those 20 years later, they look and feel ‘old’ – so who would be able to tell they were reproductions, other than those dealers who have been around for 30 years and know of these types of reproductions?” she explains.

In order to identify whether or not a piece could be a reproduction, antique and vintage dealers rely on provenance – that is, established evidence of origin and a clear ‘chain of custody’ – as well as technical knowledge of jewellery, history, and gemmology.

“Mistaking reproduction for a genuine antique is a common error,” says McAndrew. “Misidentifying a style can, in some cases, be a matter of opinion, but you can also have a diamond ring that is hallmarked ‘Chester 1890’ and another the exact same hallmarked ‘Chester 1930’.

“Tastes and styles didn’t suddenly stop and start, but ebbed and flowed with some modifications; this is where the confusion between ‘Retro’ and Art Deco arises.”

Keshett’s Crowther begins the authentication of jewellery first by examining the method of manufacturing, the materials used, metal purity, gemstones used, and cut styles, all of which can indicate the period of production, as well as stamping, hallmarks, purity marks and makers’ marks.

“There is a plethora of reproduction jewellery in circulation. Many pieces are set with genuine old-cut diamonds and others with ‘new’ old-cut diamonds.

“These items are often made with silver overset on gold in the Georgian/Victorian manner, or are in ‘aged’ platinum to give the appearance of an early 20th-Century antique. It is vital to have education and exposure to genuine items to identify these fakes,” Crowther says.

An education in gemmology is of particular use, as certain gemstones are easily dated.

“There was no Madagascan or Vietnamese ruby before the 1940s, and no hydrothermal emerald prior to 1960 – so [pieces set with these gemstones] should lead you to conclude that you have an old setting with a replacement stone, not an antique in its entirety,” she explains.

Another example is salt-and-pepper diamonds, which are exclusively used in modern jewellery, according to Wyatt.

“Similarly, if someone tried to sell you an Art Deco piece with a tanzanite in it, you would know the original gemstone was replaced with tanzanite or that the piece is a reproduction, because tanzanite wasn’t discovered until 1967,” Wyatt explains.

Tsavorite garnet is another ‘indicative stone’, as it may be used to imitate demantoid garnet.

“We know Tsavorite garnet was discovered in 1967 in Kenya, whereas the initial source of demantoids was Russia. Mining stopped there in 1917 due to the Bolshevik Revolution, and has only recently begun again. Demantoid garnet has also recently been found in Africa,” says Wyatt.

“Learning gemmology pays off every day in this way – it’s like being a detective.”

|

| Above: Late Victorian Brooch, Kelpners |

|

| Above: 1960s Cartier Griffin Brooch |

The Gemmological Association of Australia (GAA) offers specialist antique jewellery courses as well as broader gemmology education, while the NCJV also offers resources for assessing antiques accurately.

On the topic of provenance, McAndrew notes, “Unfortunately or many people, a family story is not provenance. As a guide, you need evidence that would hold up in court.

“Stamps, assay marks and hallmarks can give you lots of information, and a Cartier or Van Cleef & Arpels makers’ mark is going to have a premium in value to anything comparable without a mark – more so if it has the original box, and even more again if the original invoice exists, though that is extremely rare.”

He adds, “High-quality antiques are harder and harder to source, especially at realistic prices.

“As a rule of thumb, there is a stock supply surplus of lower-end antique jewellery and a deficit of higher- end antique jewellery.”

When sourcing antique and vintage jewellery at auction, Wyatt cautions that many pieces are not guaranteed.

“You must check the fine print of the auction,” she advises. “Auction houses don’t make mistakes deliberately, but because they have a high volume of product things can be missed.

Or, they may rely on the specifications for a piece that were provided to them by a reputable, frequent seller – and that person could have made a mistake.

“This is why it’s so important to be a gemmologist, particularly for antiques. You need to know what you’re buying. As a retailer, the buck stops with you and by law you must guarantee what you sell to the public.”

Sourcing pieces has been particularly challenging during the pandemic.

“Obtaining good quality antique pieces has been increasingly and frustratingly difficult, as our antique dealers have not been able to go overseas to source stock,” says Kalmar.

“Finding antique pieces in good condition is hard enough, and although repairs and restoration are usually required over the years, and we ourselves do this, finding pieces without lead solder, or incorrect diamonds such as a small brilliant cut instead of a genuine antique rose cut, is becoming difficult.”

Yet despite these challenges, Crowther offers a positive counterpoint: the increased globalisation of the antique and vintage jewellery trade, through new technology.

“The marketplace is now less regional and more global – perhaps not right now due to the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic, but in normal circumstances we can

cast a very wide net in our search for fine antique jewellery,” she notes, adding that repair techniques have also substantially improved, leading to a greater abundance of “unobtrusively restored” genuine antique and vintage pieces.

“There are also many more selling platforms and so it is easier to find items – and with valuer education increasing, it is also easier to have items properly authenticated,” she says.

McCabe agrees: “Because of COVID-19, our overseas suppliers – many of which we have had relationships with for more than 30 years – were not able to visit us as they normally would.

“That required them to upgrade and provide us details of their goods online – which brought us closer to the source than ever before.

“We can view things online and be the ‘first in line’ with the rest of the world, as opposed to one of the last on the list for a supplier’s Australian trip, being based in Adelaide – which is a much smaller market than the eastern states.”

However, the supply chain is not the only part of the vintage-and-antique jewellery category that has been digitally transformed.

The impact of e-commerce

The past five years have seen the proliferation of online jewellery sales. The antique and vintage category is no exception – both in terms of sourcing pieces and retailing to the public.

“Before the internet and online selling and buying, the choice of dispersion of an estate or a collection was limited to selling to a shop, dealer or an established bricks-and-mortar auction house,” McAndrew explains.

|

| Above: 1890s Carlo Giuliano Renaissance Revival Brooch |

|

| Above: 1890s Archaeological Revival Necklace |

“But with the wide choice available nowadays online, the stock has been ‘thinned out’ making sourcing so much harder. Estates are generally smaller nowadays too – a look through old auction catalogues makes this very apparent!”

Conversely, consumers’ increasing embrace of online jewellery purchasing has also been something of a boon for retailers, particularly during the COVID-19 restrictions in 2020.

This digital ‘secondary market’ now comprises online auctions, small-scale and consumer-to-consumer sellers using Etsy and other apps, as well as specialised e-commerce retailers such as Omneque.

Launched in late 2020, the UK-based website sells antique and vintage pieces – both ‘signed’ and ‘unsigned’ – which have been sourced and authenticated by jewellery historian and museum curator Vivienne Becker and fine jewellery specialist Joanna Hardy.

Following authentication, pieces are then sorted and sold as part of themed biweekly collections.

While a new business, Omneque’s presence in the market indicates the new potential of online antique and vintage jewellery sales, as well as the importance of establishing trust through expert authentication.

Further illustrating the value of the antique and vintage jewellery market, in February 2020 international diamond trading service Rapaport launched its Rapaport Jewelry Catalog (RJC) platform, exclusively for estate jewellery and natural pearls.

RJC allows “retailers and dealers [to] trade with each other as well as with consumers”.

“I think that we have a very different landscape ahead of us now,” McAndrew says.

“The public, and especially the older generation, have become more accustomed to buying online and should this trend continue – and it probably will – jewellery sales should benefit.”

He adds, “For established jewellery businesses with a known reputation, this could bring a new stream of income.

“Backed up with a valuation by an NCJV- registered valuer, consumers will have more trust and be more likely to purchase something online depending wholly on the description. Online selling is the trend, and the trend is your friend.”

However, Wyatt stresses that there are risks for consumers purchasing antique and vintage jewellery from unknown online sellers without the appropriate credentials.

“I find that jewellery online is often misdescribed. Whether it’s intentional or unintentional, the words ‘antique’, ‘vintage’, and ‘Art Deco’ are often misapplied. Art Deco in particular is a very abused term,” she tells Jeweller.

“There’s no oversight, and it becomes ridiculous – try searching ‘Art Deco engagement rings’, or ‘antique Art Deco’. Even if it is a genuine Art Deco piece, it would only be antique if it was made in 1920. As specified by law in Australia, antiques must be at least 100 years old.

“There are online retailers who will say anything to sell a product, and a lot of people just don’t have a good understanding of antique and vintage jewellery,” Wyatt adds.

Still, Crowther believes times are changing, with consumer knowledge – particularly around the difference between authentic pieces and reproductions – significantly improving.

Making the sale

While antique jewellery tends to be deliberately sought out by passionate consumers, marketing and presentation are still an important part of the sales process.

With online stores focused on grouping pieces into themed collections, bricks-and-mortar stores such as Gerard McCabe take a more traditional approach, including special in-store events and eye-catching window displays.

“Our Adelaide Arcade window is where all the antique pieces go, and that’s our most popular window by far,” says Justin McCabe.

“People know it for being unique and different, so whenever they walk through the Arcade they take a peek in the window to see what’s new!”

Engagement customers, in particular, may also find antique pieces when searching for ring inspiration via Instagram or Pinterest.

When serving customers, McCabe advises staff to carefully explain the requirements of owning antique and vintage jewellery.

“Having old pieces comes with the charm, but it also comes with the responsibility of something that has been around for 80 or 100 years – we hand that responsibility over to you!” he says.

“Staff have to discuss maintenance. All pieces need maintenance over their lifetime, but it’s harder to explain that this piece has already had some wear, and so the customer has to take responsibility for how they are going to wear it. It’s not as easy as just buying a ring.”

Crowther agrees, noting that while public awareness of the difference between original antiques and reproductions has improved, “It could be a challenge to explain that some items, due to age and frailty, are only suitable for occasional wear – particularly when customers had observed stronger reproduction pieces being worn by many daily.”

Still, for those customers who are drawn to antique and vintage jewellery, extra care and maintenance is a small price to pay for the privilege of owning a uniquely beautiful piece of wearable history.

IMAGE GALLERY

|  |  |

| Above: 1860s Victorian Locket | Above: 1820s Georgian Necklace | Above: 15th Century Ruby and Diamond Ring |

|  |  |

| Above: 1870s Mid-Victorian Pendant, Gerard McCabe | Above: 16th Century Renaissance Pendant | Above: Art Deco Ring, Keshett |

|  |  |

| Above: Vintage 1920s Brooch, Keshett | Above: 1980s Cartier Seahorse Brooch | Above: 1860s Victorian Brooch |

Read eMag

Hover over eMag and click cloud to download eMag PDF