CLICK ITEM TO JUMP TO RELEVANT SECTION

I N F O C U S

» The value of luxury

» Creative strategy

» Pandemic potential

» The making of a luxury titan: Aquisitions & Milestones

» Fresh focus: Remaking Tiffany & Co.

Most people are astonished by the size and dynamics of the luxury market. Intuitively, they assume luxury is a niche business – even people who work for luxury brands share this outlook.

But what many underestimate is a luxury brand’s enormous value creation potential.

This year, 2021, marks a historic moment for the luxury industry. All brands are hoping for better performances than last year and a speedy recovery for the European and North American luxury markets.

Both regions fared poorly during the pandemic, with some categories losing 50 per

cent or more of their market in these geographic regions, which many of the world’s most- admired luxury brands call home.

However, with the pandemic still raging across the first quarter of 2021, and most key European markets in strict lockdowns, the news that Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton (LVMH) became Europe’s most valuable company might have come as a surprise.

According to data analyzed by Finaria, the French luxury conglomerate reached a staggering $US319.4 billion (€264.6 billion) as of February 26, 2021, surpassing Nestlé, the Swiss food giant.

What’s driving this all-time-high valuation is how the luxury group used 2020 better than other luxury houses and put itself in the pole position for when the markets returned to – relatively – normal trading.

In short, their strategy execution is a masterpiece of extreme value creation from which other brands can learn.

What many businesses don’t fully understand is that consumers don’t buy luxury for the product itself, but for the brand’s exclusive value – which I describe using the term ‘Added Luxury Value’ (ALV).

ALV is fascinating yet at the same time tricky. It is a value that results from psychological effects that make our brains attribute positive aspects – such as higher attractiveness, more expertise, a better life, and more self-esteem – to a person who buys or showcases a luxury item or brand.

In other words, a luxury handbag or luxury watch ensures you are perceived as smarter, more attractive, and more fun to be with, according to my research.

It is an automatic, archaic response in our brains that we cannot deny. Studies in Europe, China, Japan, and North America confirmed that the ALV effect is universal – regardless of how much we like luxury and independent of age or other variables.

Even the product is mostly irrelevant, as this desire is driven primarily by the perceived story about the brand.

Hence, brands with powerful stories that create desire can add significant premiums due to the rare value they produce; it is not only the raw materials, but what the branded product represents, that the consumer purchases.

If your business’ brand creates high perceived consumer value, you can price for it and achieve profitability far beyond other categories; conversely, if brands cannot develop powerful stories, offer consistent experiences, or price their products correctly, ALV either does not develop or collapses completely.

And once it’s gone, it rarely returns.

That is why many brands in the luxury sector decline quickly or never take off at all – managing ALV is a core task in luxury, and few brands spend the proper time on it.

Unsurprisingly, LVMH is a master of storytelling and brand experience creation. Its founder and CEO, Bernard Arnault – who briefly became the world’s richest man in May – famously described luxury as “the ability to create desire”; the greater the lust, the higher the value creation.

In turn, more customers flock to the brands with the highest value creation and are willing to pay prices that correspond to that value.

|

Above left to right: Tiffany & Co earrings; Dior Rose de Vents campaign |

Creative strategy

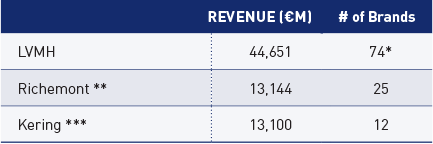

| TABLE 1: LVMH VS KERING & RICHEMONT Revenue of Europe's largest luxury groups, as at FY2020. |

|

* Excludes Tiffany & Co. which was acquired in January 2021.

** Richemont does not have a Wines & Spirits, Cosmetics & Perfume, or Selective Retailing division; however, it does have an Online Retail division *** Kering does not have a Wines & Spirits, Cosmetics & Perfume, or Selective Retailing division.

Jeweller Research |

So how is that value achieved? The answer is with a combination of the best managers in luxury and uniquely talented creatives like Dior’s Kim Jones and Louis Vuitton’s Virgil Abloh.

A good example is the acquisition of Rimowa in October 2016. Before LVMH controlled the luggage brand, it was without a clear profile or quality brand storytelling.

It overemphasised its heritage – displaying almost a complete lack of innovation – and exclusively sold products wholesale, with little oversight of how they were merchandised or marketed. This impacted consumers’ ‘brand experience’ significantly.

As CEO, Alexandre Arnault – Bernard’s 29-year-old son, who reportedly convinced his father to pursue the acquisition – cleaned up the 122-year-old brand’s distribution, removing wholesalers and promotions, significantly increasing prices, and making the brand a disruptive force.

Because of Rimowa’s efforts, carry-on luggage became as desirable as handbags for the first time in history, with seasonal collections that created the urge among wealthy travellers to showcase their newest and latest Rimowa holdalls.

The Off-White x Rimowa transparent trolley quickly became an instant hit, as did a collaboration with streetwear brand Supreme.

Then, with travel limited during the COVID-19 pandemic, Rimowa switched to backpacks and more practical items that people could use every day.

As a result, Rimowa became the perfect example of how a lagging brand can transform into a creative luxury powerhouse with a compelling brand story.

During the pandemic, LVMH acquired the famed jeweller Tiffany & Co. I expect the company to give the brand a complete transformation similar to Rimowa’s, which will breathe new life and significant growth into the iconic American brand which already enjoys massive appeal in Asia.

With an injection of creativity and ‘experience creation’, as well as more coherent pricing and assortment strategies, Tiffany will have enormous potential to expand. Notably, Alexandre Arnault left his CEO role at Rimowa earlier this year to join

Tiffany & Co. as its executive vice-president of product and communication.

In March, LVMH named Ruba Abu-Nimah – a creative director, design and experiential consultant – as Tiffany’s creative director, with Cartier’s Nathalie Verdeille as vice-president and artistic director of jewellery and high jewellery, appointed in July.

|

| Above: Bulgari |

|  |

| Above: Tiffany & Co. | Above: Tiffany & Co. |

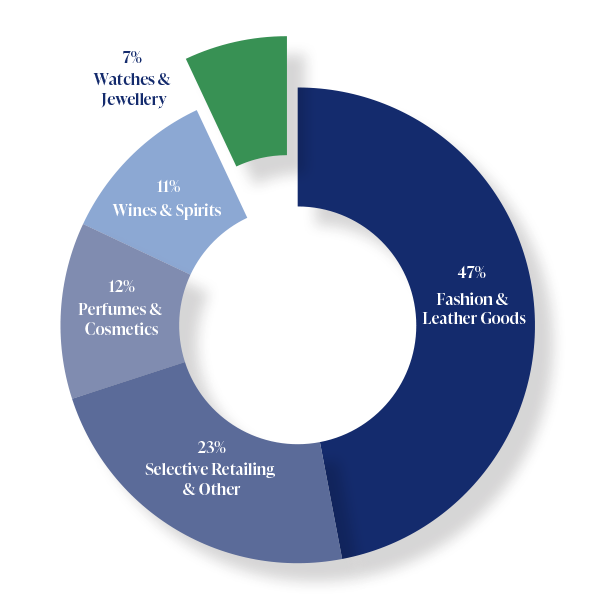

CHART A + TABLE 2: LVMH Composition by product Category & Revenue   |

Unlike many other luxury houses, LVMH has refrained from lowering prices or from promoting during the pandemic – a strategy that I suggest is the best practice for luxury brands.

In fact, brands like Dior introduced price increases, reflecting the extreme value its brand creates.

Another of LVMH’s strong characteristics is that it isn’t afraid of making tough decisions.

One such decision was putting Fenty – the glamorous fashion house it created together with pop singer Rihanna – on hold in February 2021.

Rumours about Fenty’s disappointing results and the high cost of establishing a new brand led LVMH to shift its focus to more promising and scalable brands for the time being.

In 2020, key LVMH brands like Dior continued to expand digitally by experimenting with newer platforms like TikTok while other luxury brands were reluctant and slow to adapt.

As such, the Dior x Air Jordan limited edition shoe created one of the highest instances of ‘digital demand’ ever, with more than 5 million people attempting to buy the shoes over the Dior website.

This increased resale prices of the limited edition shoes to between $US10,000–$20,000, depending on the platform. That initiative alone shows the power of ALV.

The ability to consistently manage a complex brand portfolio with the primary focus of creating desire and ALV – and translating that extreme value into higher prices explains LVMH’s success story and has driven its market valuation to unprecedented heights.

The company’s brands have been among the best managed during the pandemic, connecting strongly with their customer groups while always innovating.

LVMH provides a lesson for other luxury brands: if you focus on the excellent execution of a strong brand story, avoid the urge to promote, and digitally engage with your customer base in tough times, then you will be rewarded in customer desire, larger revenues, and higher profitability.

The current surge behind LVMH reflects that investors believe the company is well-positioned to lead, even in a pandemic.

Do people have that kind of faith in your brand?

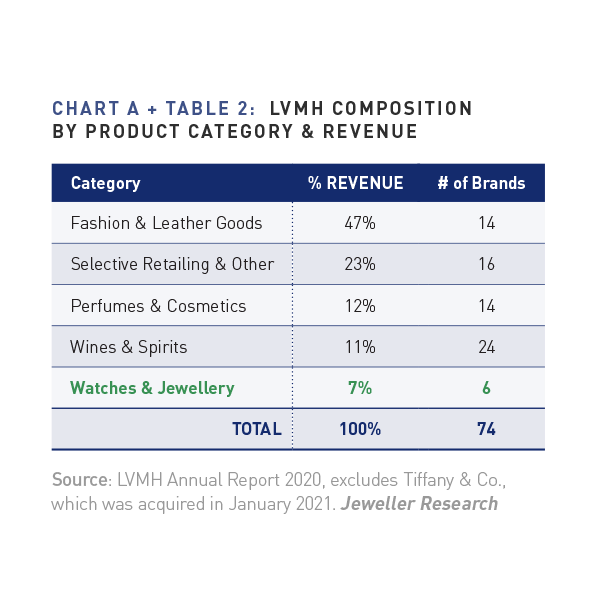

CHART B: LVMH Growth over time – Revenue/Sales & Number of Stores

Sources: LVMH Annual Reports (2000–2020), Jeweller analysis. | Note: Store count unavailable for 2000–2001, Jeweller Research |

| 1969 | Businessman Bernard Arnault acquires Boussac, the bankrupt parent company of Christian Dior, for $US60 million |

| 1987 | Louis Vuitton merges with Moe¨t-Hennessy to form LVMH in

a $US4 billion deal; disputes immediately begin over control of the companies and Henry Racamier, long-term CEO Louis Vuitton, invites Arnault to acquire stock to secure his position |

| 1988 | LVMH acquires couture fashion house Givenchy from its founder, Hubert de Givenchy; it already controls Parfums Givenchy

via subsidiary Veuve Clicquot |

| 1990 | Following a legal battle between Arnault and Racamier, Racamier steps down from LVMH |

French businessman Yves Carcelle joins LVMH as strategic director; under his leadership, the company invests in marketing through PR stunts, celebrity endorsements, and – most effectively – generating artificial scarcity |

Italian men’s apparel and leather goods brand Berluti and French-Japanese fashion brand Kenzo are folded into the group |

| 1993 | French perfume, cosmetics, and skincare brand Guerlain – founded in 1828 – is sold to LVMH by the Guerlain family |

1994 | Founded in 1945, Paris-based fashion and leather goods brand Ce´line is fully integrated into LVMH at a cost of FR2.7 billion; Spanish fashion house Loewe, founded in 1846, is also acquired |

| 1996 | LVMH invests $US2.6 billion to acquire a 61 per cent stake in DFS, a specialty retailer catering to international travellers (duty-free shopping); it also acquires winery Chateau D’Yquem |

1997 | LVMH acquires French perfume and cosmetics retailer Sephora for $US267 million |

| 1998 | The Asian economic crisis eats into sales, with the Specialty Retail division recording a 22 per vent decline in revenue for the first nine months of the year; however Arnault is undeterred and proceeds with the acquisition of Le Bon Marche´, an exclusive Paris retailer, as well as champagne brand Krug |

| 1999 | The conglomerate pursues even more expansion, with

the purchase of several US cosmetics companies and the establishment of its Watches & Jewellery division including TAG Heuer, Zenith, Ebel, and Chaumet; LVMH establishes US headquarters in New York |

LVMH sells its stake in Gucci to Pinault-Printemps-Redoute (now Kering) for $US806 million |

2000 | LVMH takes a controlling interest in Italian fashion houses Emilio Pucci and Fendi and a minority stake in Rossimoda, later acquiring sole ownership |

2001 | LVMH acquires a 55 percent stake in iconic Art Deco-Art Nouveau French department store La Samaritaine and its real estate assets for €256 million; the store falls into disrepair in 2005 and LVMH later increases its ownership to 100 per cent in 2010 |

The conglomerate acquires an 89 per cent stake in US fashion brand DKNY, later selling it for $US650 million |

| The year also marks the start of LVMH’s attempt to take a controlling interest in Herme`s; however, its accumulation of shares via subsidiaries is later found to breach French financial laws, leading LVMH to divest its 23.1 per cent stake in 2015 |

| 2005 | The flagship Louis Vuitton 'Maison' opens on the Champs-Élysées in Paris to great fanfare. LVMH's retail distribution network reaches 1,700 stores worldwide |

2011 | In a $US5.2 billion deal, LVMH acquires a controlling stake in Italian jewellery brand Bulgari from the Bulgari family |

2013 | LVMH spends €2 billion to acquire an 80 percent stake in the Italian luxury textile and ready-to-wear company Loro Piana |

2015 | Furthering its financial interests in the jewellery sector, LVMH purchases a minority stake in Italian jewellery brand Repossi, later increasing its stake to 69 per cent |

2016 | A €640 million deal sees LVMH take an 80 per cent stake in German luggage Rimowa |

2017 | LVMH makes its most expensive acquisition yet, spending $US13.1 billion to take control of Christian Dior |

2019 | The conglomerate announces plans to acquire US jewellery company Tiffany & Co. for $US16.2 billion; however, due to the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic, the deal is later renegotiated amid legal wrangling |

| 2021 | LVMH completes its acquisition of Tiffany & Co. for $US16 billion, its largest deal to date |

| Following an $US894 million refurbishment to turn it into a ‘retail destination’, La Samaritaine is re-opened in Paris |

| Jeweller's timelines are compiled through comprehensive research to demonstrate a full sequence of events. They serve as a record of significant events within the watch and jewellery industry. | Jeweller Research |

Since acquiring the American jewellery juggernaut in January 2021, LVMH has undertaken a full-scale transition of its executive leadership. Veterans of its other divisions – including senior management from Louis Vuitton and Rimowa – have taken the reins, with creative positions filled by executives from brands such as Cartier and Revlon. Among plans for store renovations and pop-ups – including the successful yellow store on Los Angeles’ Rodeo Drive, to accompany the Tiffany Diamond – LVMH has also indicated it will invest significantly in expanding the Tiffany & Co. brand worldwide. Jean-Jacques Guiony, chief financial officer LVMH, told investors earlier this year, “Integrating Tiffany is very important to us... [The company is] a big acquisition for us [and] our number one priority. “It will take years to do what we want to do with this brand, from a distribution, merchandising, and marketing viewpoint. It is a lot of work – we are committed to doing it.” High-profile new celebrity spokespeople have been announced in recent months, including actresses Anya Taylor-Joy (top right) and Tracee Ellis Ross (top center), Olympian Eileen Gu, Blackpink singer Roseanne ‘Rose´’ Park (top left), and performer Jackson Yee. |

Under New Management

Michael Burke |

Anthony Ledru |

Alexandre Arnault |

Ruba Abu-Nimah |

Nathalie Verdeille | CHAIRMAN Also chairman, Louis Vuitton | CEO Former executive vice-president of global commercial activities, Louis Vuitton | VICE-PRESIDENT OF

PRODUCT & COMMUNICATION Former CEO, Rimowa | EXECUTIVE CREATIVE DIRECTOR Former creative director, Revlon | VICE-PRESIDENT /ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF JEWELLERY Former creative director, Cartier |

Jeweller Research |

READ EMAG