Let’s say you are the buyer, or a key decision-maker in a jewellery store, and over the past few years an increasing number of shoppers are asking about ‘responsibly sourced’ jewellery.

Let’s say you are the buyer, or a key decision-maker in a jewellery store, and over the past few years an increasing number of shoppers are asking about ‘responsibly sourced’ jewellery.

You know it’s a topical issue – no different to eco-friendly and sustainable products in other retail categories such as consumables.

You’ve also heard that it’s complex issue. However, your intention is to begin offering, or continue selling, products that are ‘responsibly sourced’, whether they be gemstones, diamonds, or other jewellery.

It’s about showing that your business has what is known as ‘CSR’ – corporate and social responsibility – across the board, even though you may only operate a small jewellery store.

So how do you go about it? What are the guidelines, and, most importantly, how can you guarantee that you are sourcing responsibly?

And just because someone says a product is responsibly sourced, does that make it true?

Defining the problem

The first issue is to work out what ‘responsibly sourced’ actually means. To the consumer, it may have many meanings.

Some might be interested in ensuring that no child labour is involved in the supply chain that produced, say, that beautiful colour gemstone or gold jewellery piece.

For other customers, ‘responsibly sourced’ might relate to the impact on the environment, say, in mining operations. Others might be concerned about human trafficking, organised crime or the involvement of extremist groups in the supply channels.

And more politically savvy people may be concerned about insurgent groups using the proceeds of mineral production to finance armed conflict.

As you are probably starting to gather, ‘responsibly sourcing’ is not as simple as it first seems.

To add more complexity to the matter, responsible sourcing is not the same as ‘sustainable sourcing’.

The former requires meeting or complying with accepted levels of ethical or trustworthy practices in areas such as human rights or pollution, whereas sustainable sourcing goes beyond compliance to engage and improve the conditions of sustainability that can include areas such as livelihoods or climate-smart practices.

So when a customer is asking you about responsible sourcing, their definition could be very different to yours – or that of your suppliers – and they could even have sustainable sourcing in their mind.

Complex Subjectivity

The one reality in all of the above is that there are so many factors involved in the adjudication of what is, and is not, ‘responsibly sourced’ that it’s impossible for there to be unanimity between consumers as to what it means. It is an entirely subjective process.

A noble concept, but subjective nevertheless! And after all that, everything remains voluntary too.

After all the above, the process and definition then becomes even more complicated when each element of responsible sourcing needs to be weighted relative to the other, and then scored to give an overall performance assessment.

It’s a process that every customer does intuitively, making it impossible for there to be unanimity between customers.

|

|

| Above: Artisanal sulphur miner, Kawah ljen Volcano, Indonesia. |

|

|

| Above: Artisanal sulphur miner, Kawah ljen Volcano, Indonesia. |

|

|

| Above: Artisanal sulphur miner, Kawah ljen Volcano, Indonesia. |

|

|

| Above: Kawah ljen Volcano, Indonesia. |

|

The little guy

One of the major issues I raise with people and groups who preach about ethics is that responsible sourcing and sustainable sourcing both ignore the fact that almost the entire focus is on the negative aspects of jewellery supply chains, rather than the incredible positives that sourcing from Third World countries can also generate.

And I say ‘Third World’ because the overwhelming production of gemstones in particular comes from impoverished nations.

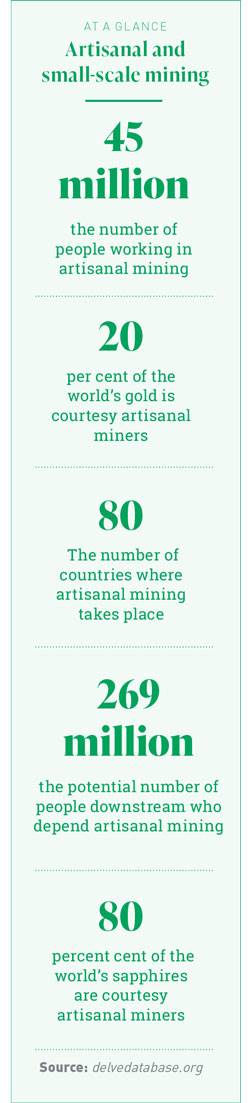

Now, here’s the rub. I say ‘incredible positives’ because 85 per cent of the global mining of gemstones is carried out by, what are colloquially known as, artisanal miners.

Artisanal mining, or small-scale mining, refers to subsistence mining by people using primarily manual means - forget machinery and automation, they work using tools such as picks and shovels. Think of the photos we’ve all seen of the Australian gold rush in the 1850s.

It’s estimated that there are 40 million people mining this way around the world, while a further 240 million people symbiotically depend on the activity.

The benefits not only accrue to these miners in the form of employment, they also accrue in terms of opportunities for others to gain skills they would otherwise not have because the large-scale mining companies are typically looking for higher levels of education and training than most of these miners could ever dream of possessing.

So artisanal miners and their families can learn how to be vendors, butchers, accountants, and even microfinance providers. The list of occupations within larger artisanal mining communities is large.

Artisanal mining operations are thriving and vibrant economies where almost all of the money earned by the workers stays within local communities and ‘in-country’ with some location-specific exceptions. For example, the ‘narcos’ using illegal mines to launder dirty money from drug sales into the US. There was a very public example of this out of Miami recently.

Contrast this to the multinationals, which enter a country, pay a small amount of taxes, employ far fewer people and then repatriate most of their profits to their country of origin and the home countries of their shareholders.

As you are starting to see, the concept of responsible sourcing is a minefield (pun fully intended!) and one which consumers will find almost impossible to navigate, let alone understand the complexity.

I have worked in the field for more than 16 years and I have trouble understanding it, so what hope has the consumer?

Fork in the road

Back to you, as a jewellery retailer who wants to do the ‘right thing’ for your customers and your business: what should you do?

The first decision is how do you find your responsibly sourced jewellery?

Whether you source it directly, or whether you buy from local or overseas wholesalers, you then have to decide whether you will advertise and promote the products as being responsibly sourced. If not, why would you bother?

Assuming your aim is to promote your own CSR values, then you will most likely promote your business – or at least some of the products – as responsibly sourced.

This leads you to another fork in the road. Will you rely on your own values and definitions, or will you rely on a supplier having third party accreditation?

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) enforces the Australian Consumer Law of which section 18 provides that “a person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive”.

Now, considering there is no single, unilateral definition for ‘responsible sourcing’ and it can mean different things to different people – I think it would be impossible for a consumer to be misled or deceived – however, I would encourage you to seek your own legal advice in that regard.

Artisanal mining operations are thriving and vibrant economies where almost all of the money earned by the workers stays within local communities and ‘in-country’ with some location-specific exceptions. d’être

But let’s say you choose to pursue some assurance from an external, third party before making claims that your jewellery is responsibly sourced.

You might look to a body such as the Jewellers Association of Australia (JAA) or the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC).

The JAA promotes itself as, “Advancing the Australian jewellery industry through representation, unity and consumer confidence” while the RJC tells us that it is “the world’s leading standard setting organisation for the jewellery and watch industry. We promote standards that underpin people’s trust in the worldwide jewellery and watch supply chain.”

How does any of this help you as the jewellery buyer or decision-maker to decide whether your precious stones and jewellery are responsibly sourced?

These two ‘official’ organisations should set your mind at ease, right? Well, a review of the JAA’s Industry Code of Conduct 2022 doesn’t engender great confidence.

Three issues often talked about in the context of responsible sourcing are mentioned without much more, requiring Code Signatories (local retailers or suppliers) to:

- Implement the procedure provided by the CIBJO and the World Diamond Council’s “System of Warranties”

to prevent trade in conflict diamonds; - Implement procedures recommended by the JAA to prevent trade in conflict gemstones and precious

metals; and, - Make every effort to deal only with companies that do not exploit children or use child labour, provide

adequate occupational health and safety conditions and respect the environment.

CIBJO and the World Diamond Council’s (WDC) ‘System of Warranties’ will be addressed below but I could find no procedures recommended by the JAA to prevent trade in conflict gemstones and precious metals.

Moreover the provision on child labour is so ambiguous as to be meaningless. There is no mention as to what child labour means specifically. What ages are included? What occupations? What even constitutes OH&S or respecting the environment? All these details are left undefined.

In other words, it appears to me that its mere virtue signaling, designed to make the JAA look as though people actually care or that organisations are honourable.

It’s window dressing, form over substance.

For anyone who might be unscrupulous or for someone that doesn’t care about the substance and importance behind these issues, it’s conceivable that JAA membership could be used to present a veneer of responsibility by promoting a company as ‘responsible’ by being a signatory to the Industry Code of Conduct.

In other words, the JAA’s Code is a waste of time for someone that genuinely cares about ‘doing good’.

|

|

| Above: Meat vendor, artisanal gemstones mines, Karakorum Range, Northern Pakistan. |

|

|

| Above: High altitude artisanal gemstones miner, Karakorum Range, Northern Pakistan. |

|

|

| Above: High altitude artisanal gemstone miner, Karakorum Range, Northern Pakistan. |

|

|

| Above: High altitude artisanal gemstone miner, Karakorum Range, Northern Pakistan. |

|

Responsible Jewellery Council

This brings us to the RJC, which has been recently hammered in the international media over its association with Alrosa, the Russian diamond mining company which is one third owned by the Russian government, and which has been accused of helping finance Russia’s recent war on Ukraine.

The RJC Code of Practices (COP) was last amended in 2019 to bring it into alignment with the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (the “OECD DDG”).

» Background reading: How responsible is the Responsible Jewellery Council?

This updated system is much tighter than the previous system and applies to gold, silver, PGM, diamond and gemstone supply chains. However, no matter how tightly regulated a system may appear, it always seems possible to find gaping holes.

Sadly, we usually find these imperfections after the fact, when a breach has already been committed.

Gemfields and Montepuez

This is where the entire concept of responsible sourcing gets murky.

For example, in 2009, a local farmer discovered a massive ruby deposit in the north of the country, in Montepuez. The find became the world’s richest ruby discovery and currently accounts for about 40 per cent of global supply.

Within months of the discovery, it’s reported that a local army General is alleged to have moved to expropriate the land and over which he subsequently acquired prospecting rights.

The local farmer received nothing for his land or for the ruby discovery and was too poor to assert his legal rights.

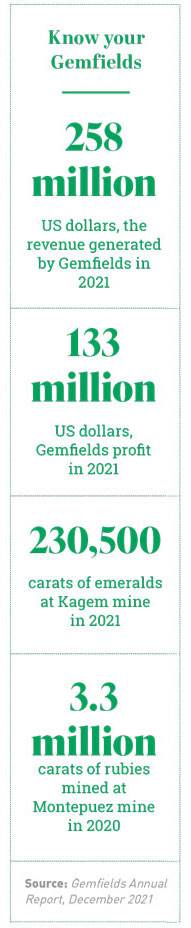

Within the space of two years, the General formed a joint venture company called Montepuez Ruby Mines (MRM), which was split 75:25 with a large-scale mining operator, Gemfields Group.

Gemfields Group is incorporated in the tax haven of Guernsey. It is listed on the Johannesburg and London Stock Exchanges.

In recent years activity at the MRM has seen increasing controversy, which has been reported widely by the world press.

Regional Protection Police and members of Mozambique’s elite military unit were engaged together with a private security firm allegedly hired by Gemfields to provide security on the mine’s concessions.

There have been allegations of murder, torture and beatings of local villagers and miners working on those concessions by nacatanas (machete gangs) and private security personnel associated with the General and Gemfields.

Leigh Day, a British legal firm that began litigation against Gemfields in the UK on behalf of scores of plaintiffs. Its cases rarely, if ever, seem to get to trial, and that is what also transpired with the Gemfields case.

Gemfields settled out of court in early 2019 for the piddling amount of $US7.8 million, in a no-fault settlement. I gather the company realises that the MRM controversies refuse to go away.

Until further updates, watch that space!

|

|

| Above: Artisanal coal scavenger, India. |

|

|

| Above: Artisanal coal scavender, India. |

|

|

| Above: Artisanal gold miner, Burkina Faso. |

|

Third party certification

This brings me back to the RJC. While it’s clear that many of the artisanal miners and villagers were illegally operating on MRM concessions, they have received much worse than a raw deal by none other than one of the world’s largest gemstone producers.

While all this is on-going, these same Montepuez rubies are being marketed to global consumers as ‘responsibly sourced’ by Fabergé, a subsidiary company of Gemfields.

Interestingly, Fabergé is a certified member of the RJC, however Gemfields is not, even though a major component of Fabergé jewellery is the gemstones and rubles mined by Gemfields.

Its website states: “Today, Fabergé is a member of the Gemfields Group – a world leading supplier of responsibly-sourced gemstones”.

Therefore, the obvious question that arises is: how can gemstones that do not seem to be sourced responsibly within the context of the RJC’s COP somehow then be responsibly sourced by its wholly owned subsidiary?

It raises many more questions around the meaning of the word ‘responsible’ and leaves us wondering how product sourced by Faberge from the MRM concessions can be considered to meet the COP requirements for certification if the circumstances under which its parent company Gemfields came to own a share in the mine has so many ethical issues – and controversies - hanging over it?

For example, is it not correct to question the manner in which the largest ruby discovery in history could somehow lead to the expropriation of land from local villagers and that these people, including the farmer who made the discovery, could receive next to nothing for his discovery?

And further, how can it be ‘responsible’ for that land to be rezoned and issued to a high-ranking government official before then being part-sold to one of the world’s largest gemstone miners?

One example of many

Let’s say you’re the buyer, or a key decision-maker in a jewellery store, and over the past few years an increasing number of shoppers are asking about ‘responsibly sourced’ jewellery.

Let’s say you’re the buyer, or a key decision-maker in a jewellery store, and over the past few years an increasing number of shoppers are asking about ‘responsibly sourced’ jewellery.

Unfortunately, this is not an isolated case.

There seems to be one rule for some of the world’s poorest – artisanal miners mining by hand and fighting to feed their families – and another rule for the large mining companies.

Recently, I was talking with a colleague who is a mining company senior executive who has spent many years supplying contract services to gold mining companies. He told me that one of the world’s largest gold miners – a Western company - had just made a substantial royalty payment to the government in one of its countries of operation.

The village immediately adjacent to the mine which generated this royalty payment has no sewerage, and barely any electricity.

I’ve witnessed this first hand. Some of the worst poverty I’ve seen in Africa has been right next to some of its biggest gold mines.

However, for some reason, it’s ‘taken as gospel’ that most Western mining companies operate responsibly because, regardless of whether this gold producer is a member of the RJC, one can almost certainly assume that gold sourced from its site is being labeled as ‘responsibly sourced’!

» Background reading: Gemfields, Fabergé and the Responsible Jewellery Council

While it’s true to say that the world’s poorest artisanal miners, which everyone seems to love taking a big stick to, are by no means perfect, there are so many issues that must be considered adjudicating on whether a mineral is responsibly sourced.

Most of these issues are continually overlooked and responsible sourcing needs to be much more holistic.

Evaluating the impacts of mining on local communities - and that’s for large and artisanal mines – must include factors such as employment, in-country and regional stability (because people are gainfully employed), environmental impacts, the opportunity for people to acquire new skills and the retention of wealth ‘in-country’.

My issue is that we all seem to be happy to attack the small guys – the artisanal miners – because they are easy to target and can’t fight back.

At the same time, we ignore the misdemeanors and perils of the larger producers because they have many more financial resources and powerful people watching their backs.

In other words, holding the largest producers to account is a much tougher task. Just look at Russian diamond mining juggernaut Alrosa, if you need an example.

'Responsibility’ sector

The RJC’s COP is clearly an improved attempt at a more stringent and responsible due diligence standard, however, no matter how rigorous people attempt to make guidelines there will always be loopholes that are in almost direct proportion to the amount of subjectivity and latitude allowed within those standards.

The subjectivity and loopholes vary from consultant to consultant and auditor to auditor and the level and extent of their life experience with the impoverished nations of the Third World. Then you can overlay the inequality of bargaining power between large and small and you can start to understand the problem.

If you’re a small miner then your capacity to argue that you are doing anything ‘responsible’ will be almost minuscule when compared to any of the world’s largest mining companies that hold certification and have powerful board members, lawyers and litigation budgets to fight anyone who attempts to take them on.

And these challenges pervade the entire responsible sourcing sector, whether that involves the RJC, WDC or CIBJO. The legislation and codes of conduct are only as tight as the interest groups controlling them will allow.

If you have powerful vested interests fighting you the entire way, the chances are that legislation or codes of practice will tend to offer leniency towards those same interest groups. At the same time, they will block every nook and cranny for those without sufficient resources to fight their case.

To see this logic in practice, it is instructive to look at the EU CAHRA legislation that came into effect on 1 January 2021. This legislation was released with much fanfare and is still trumpeted by the international responsible sourcing groupies as being the high-water mark in global responsible sourcing legislation.

The legislation followed the OECD Due Diligence Guidance, however, when the legislation was published, it applied only to the 3Ts and G - the 3Ts being tin, tantalum and tungsten and the G being gold.

A senior OECD official recently wrote to me and said that the Guidance was limited to these minerals because it takes time to get the industry prepared.

|

|

| Above: Underground silver miner, Cerro Rico, Bolivia. |

|

That’s accepted, but I pointed out and suggested to him that the draft legislation was first produced in 2017 and that the responsible sourcing push by legislators around the world had been happening since the Obama administration began in 2010.

Further, that the OECD Guidance was originally finalised in 2013.

How much ‘time’ is enough? And how much time should be enough?

This is to assume that the participants involved are genuine about the process and not merely virtue signaling. A mounting body of platitudes and evidence seems to support the latter.

The apparent lunacy of it all is then amplified by the fact that the EU CAHRA legislation has no enforcement or penalty provisions and that any changes to this may be considered when a review of the legislation is slated for 2023 or 2024.

To quote responsible sourcing consultants and risk management firm, Achilles, when the new CAHRA legislation was published: “Both the law in the US and EU currently lack any real teeth. However, it is expected that sanctions or penalties could be introduced in Europe at a later stage if little progress is made, potentially following its first review in 2023.” [Emphasis added].

Biggest question for retailers

This brings us all the way back to the original question: How can I do ‘good’ and buy responsibly sourced jewellery?

If I’m being honest, I still can’t answer that question. Clearly if you’re a member of the JAA or RJC then there will be some obligations that you will need to follow.

If you have powerful vested interests fighting you the entire way, the chances are that legislation or codes of practice will tend to offer leniency towards those same interest groups. ‘in-country’ d’être

However, whether there are penalties for failing to do so is another question entirely. On the other hand, if you’re not a member, it’s pretty much happy days – do what you like!

Regardless of whether you are a member of the JAA or RJC or not, then in my view it matters not as to whether the gemstones you are buying have been bought responsibly. What really matters is visiting the communities where the resources are produced and building some sense of understanding as to what positives or negatives will come from your buying decision.

No matter how hard people try to package up and present responsible sourcing as the solution to difficult problems around the world, these things still come back to the same things as they always have.

The big guys write the rulebook and the little guys get pushed around and kicked out.

If legislators around the world were serious about responsible sourcing in the minerals industry there would be no exclusions by legislators for any mineral. The rules would be enforced equally whether breaches relate to the artisanals or the largest companies.

At the moment this isn’t happening.

There is a reason that not all minerals fall within legislation and COP guidelines and it’s because some people are more powerful than others. And as many times as they may say it, this has nothing to do with legislators and policy-makers not having had enough time to get it right and everything to do with politics and influence.

I believe that the existing system that has arisen is fundamentally flawed and will never be fixed. But that’s a discussion for another time.

In the meantime, you may now be wondering whether ‘responsibly sourced’ includes enormous profits being repatriated back to wealthy countries from impoverished countries or, if it means giving some of the poorest families in the world the chance to survive and prosper?

Whatever your intent, I wish you all the best in trying to ensure your responsibly sourced jewellery and gemstones are actually ‘responsibly sourced’, depending on what that means to you, and your customer.

Good luck!

READ EMAG