Extraordinarily valuable and remarkably rare, fancy colour diamonds are among the most passionately discussed topics in the jewellery industry.

With that said, few ever stop to ask an important question, namely – what makes a red, pink, or blue diamond ‘fancy’?

Furthermore, when is a colour diamond not a fancy colour diamond? Or, put another way, is there such a thing as ‘non-fancy’ colour diamonds – or are all colour diamonds innately fancy?

The descriptor is an unusual choice of wording; however, as it appears on the reports issued by the world’s leading authority, the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) - it’s the industry standard.

The demarcation of these stones is a complicated matter; however, the most important concept to understand is that the grading system places great significance to the ‘strength’ of colour.

To qualify for the ‘fancy’ moniker, diamonds must display a colour stronger than the Z grade.

For the diamonds that reach these parameters, there are six distinct categories of which to be mindful - fancy light, fancy, fancy intense, fancy dark, fancy deep, and fancy vivid.

The GIA assesses three core characteristics - hue, tone, and saturation - to determine which of these six categories within which a stone is classified. There are six colours that make up the 27 distinct hues.

While there is much more to be said about the intricacies of the study of these colour diamonds, the core principle to understand is that the term ‘fancy’ is restricted to the rarest of stones that display stronger colour than those on the K-Z scale.

With that said, there is still quite a range of differing diamonds within that ‘fancy’ territory - could it be said that the term is therefore redundant?

Put another way, if there are six distinct classes of diamonds that can be classified as ‘fancy’, why do we bother with the term ‘fancy’?

For the sake of simplicity, why not call it a vivid or intense colour diamond rather than a fancy vivid or fancy intense colour diamond?

While it’s a reasonable question to ask, it is worth noting that such a dramatic change would be chaotic for the market. All pre-existing reports would be outdated, with hundreds of millions of dollars at stake.

With that said, the more succinct the language, the better! As Oscar Wilde once said: “If I had more time, I would’ve written a shorter letter.”

Despite this apparent redundancy, many jewellers continue to use the term ‘fancy’ coloured diamonds to adhere to the industry standards - and accepted terminology - set by the GIA.

Not all industry figures are so quick to ‘get in line’; however, and what would appear to be an increasing number of jewellers – including several major retailers – are dropping the term, particularly when dealing directly with consumers.

So, who is right in this war of words?

|  |  |

The Aurora Green 5.03-carat fancy vivid green diamond

SOLD US$16.9 million @ Christie's | Argyle Tender; Lot 8 0.64-carat fancy gray-blue diamond Glajz | Magnificent Jewels, Lot 1882 5.29-carat fancy intense green diamond

SOLD US$3 million @ Sotheby's |

| | | |

History lesson

Before we explore the pros and cons of each case, it’s essential to understand how and why the term ‘fancy’ came about.

While the fancy colour diamonds that command mind-boggling prices at auction today were formed billions of years ago deep within the Earth, the first extensive documentation of these natural wonders dates to the Indian subcontinent in the sixth century.

At the time, there were strict limitations on who could possess fancy colour diamonds in India – then known as Bharat – defined by social class.

A ruler could, of course, possess any diamond he wished.

Priests were limited to white, clear diamonds, while warriors and landowners were permitted to own brown diamonds, described as ‘the colour of the eye of the hare’.

Nearly 1,000 years later, the rough that would become the Hope Diamond was discovered in the Kollour Mine in India.

Today, the 45-carat dark greyish-blue stone is regarded by many as the most famous diamond in the world.

The origins of the diamond are somewhat unclear; however, it’s believed the stone was obtained by French gemstone merchant Jean-Baptiste Tavernier around 1666.

Tavernier travelled with the rough to Paris, where it was cut into a crude triangular shape and named the Tavernier Blue.

This diamond was eventually sold to King Louis XIV; however, the circumstances of the sale are also unclear.

In 1678, King Louis XIV commissioned court jeweller Jean Pitau to recut the Tavernier Blue, resulting in a 67-carat diamond which royal inventories listed as the Blue Diamond of the Crown of France.

Fancy colour diamonds were particularly popular with French aristocrats, and diamond cutters would use the term ‘fantaisie’ when describing these stones.

When translated to English, fantaisie can be interpreted two ways – ‘fancy’ and ‘fantasy’.

The term fantaisie was used by these craftsmen because of the ‘otherworldly’ nature of these diamonds. Indeed, when compared with white diamonds, fancy colours do feel like the stuff of fiction.

Of all the diamonds mined each year, a mere 0.01 per cent are fancy colour. That’s roughly one in every 10,000 carats extracted from the Earth!

Nearly 300 years later, a US jeweller – Robert Shipley – established the GIA in 1931, hoping to address what he perceived as a lack of scientific expertise within the industry.

In 1953, the GIA developed its International Diamond Grading System and introduced the four Cs – colour, clarity, cut, and carat. The first diamond reports were issued two years later.

According to a 1994 issue of Gems and Gemmology, it was around this time that interest first began to increase in fancy colour diamonds.

“The GIA’s interest in the colour origin of coloured diamonds was initially sparked in 1953 when staff members were first shown diamonds treated to ‘yellow’ with cyclotron irradiation,” the report reads.

“As news of the availability of cyclotron-treated diamonds spread in the trade, the GIA began to receive large numbers of colour diamonds from clients wanting to know whether the colour had been altered by laboratory irradiation and annealing.

“Almost as soon as it was introduced in 1956, the GIA’s origin of colour report began a process of the systematic standardisation in describing coloured diamonds.”

The report clarifies that the term ‘fancy’ was first used on GIA reports to describe natural faceted diamonds that exhibited colour appearance when viewed either face-up or simply displayed any colour other than yellow or brown.

The GIA’s colour grading system was further refined in the 1960s and 1970s, with several ‘master comparison stones’ used to judge other diamonds against a ‘standard’.

Interestingly, much of this research was spurred by frustrations within the industry about the lack of a standard definition for a ‘canary’ coloured diamond – further highlighting the timeless importance of language and terminology.

GIA researchers established boundary distinctions and expanded the collection of master stones; however, there were significant hurdles to overcome – namely, the lack of availability of master stones to cover the wide variety of diamonds that occur in nature.

“Grading the colour of coloured diamonds is one of the greatest challenges in gemmology. The description must be a thoughtful blend of both art and science,” the report reads.

“It is not an easy process. It requires a robust system with consistent standards. A fancy yellow diamond must be the same yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

"Finally, to neglect history and tradition, or to distance ourselves from the mystique and romance associated with natural-colour diamonds, is to do injustice to their beauty.”

|

The Argyle Violet 2.83-carat fancy deep grayish bluish violet diamond

LJ West | The Golden Empress 132.55-carat fancy yellow diamond

Graff Diamonds | The Graff Pink 23.88-carat flawless fancy vivid pink diamond

Graff Diamonds |

| | | |

Hit the books

While these details are fascinating, they don’t answer the initial question – why was the word ‘fancy’ adopted?

Jeweller contacted the GIA for an explanation and intriguingly, researchers were unable definitively to answer the question. What they were able to reveal; however, was that the term predates the GIA.

The GIA was able to identify classic works published in 1751, 1839, and 1874 which describe known colour diamonds without the use of the term ‘fancy’ or ‘fantasie’.

The authors of these texts describe the colour of these diamonds to the best of their ability, without the added benefit of standardised terminology.

The earliest book the GIA was able to uncover using the term ‘fancy’ was ‘The Diamond’, written by Wallis Richard Cattelle and published in 1911.

“Other things being equal the relative market values of colour in the diamond are about as follows: Fancies: emerald-green, red, sapphire blue, pink, orange, tints of violet-blue and blue, canary, black, and brown,” the book states on page 149.

The earliest use of the term ‘fancy’ by the GIA appears in a September 1935 issue of Gems and Gemmology.

“Colour in a marked degree is normal to the latter two species, but ‘fancies’, the "pierres de fantaisie" of the French, that is diamonds of vivid colour when cut, are among nature's rarest products,” writes Sydney Ball.

A translation of the French term ‘pierres de fantaisie’ to English reads ‘fancy stones.’

The earliest known GIA diamond grading report to use the term ‘fancy’ is dated October of 1954 – a fancy light green stone.

|  |  |  |

Oppenheimer Blue This 14.62-carat rectangular-cut diamond fetched a record-breaking US$57.5 million (AU$79.5 million) in 2016. | De Beers Blue The world’s largest blue diamond, the De Beers Cullinan Blue, was sold at auction for $US57.47 million ($AU80.96 million) in 2022. | Blue Moon of Josephine This 12.03-carat fancy vivid blue diamond set a price-per-carat record at auction for any diamond or gemstone when it sold for US$48.5 million (AU$67.5 million) in 2015. | Fortune Pink It was hoped that the 18.18-carat pear-shaped fancy vivid pink diamond would achieve a historic return; however, it wasn’t to be. It returned $US28.8 million ($AU44.79 million) in 2022. |

What did we learn?

So, what is the outcome from this history lesson? The GIA doesn’t claim to have coined the term ‘fancy colour diamonds’ – it merely standardised the language that was already widely used within the jewellery industry.

With that said, the GIA’s authority is in the realm of science – and the cold, hard facts of science are often (appropriately) thrown to the wayside in the relationship in the business world, including between retailers and consumers.

So, while it may be appropriate for members of the diamond industry to adhere to the term ‘fancy colour diamonds’ for the sake of standardisation, should retailers move on to something more straightforward?

Owner and founder of the House of Cerrone, Nic Cerrone, suggested that adhering to the standards set by the GIA was an approach that has worked well for his business.

“I see grading companies using the word ‘fancy’ to state that the diamond is coloured,” he tells Jeweller.

“We convey the exact information and terminology that is stated on the certificate of the diamond to our customers.”

Based in Melbourne, James Temelli is the marketing manager of Temelli Jewellery, specialising in bespoke creations featuring rare diamonds and gemstones.

Temelli suggests that the terms used to describe these stones should be adjusted depending on the audience.

“Fancy colour diamonds is a term often used in the trade and often overseas when describing coloured diamonds with a fancy grade - as opposed to an unappealing colour tone,” he reveals.

“In a conversation with a customer, or in a marketing context, we tend to use simpler terminology, that is, ‘coloured diamonds’ without the ‘fancy’. Keeping it simpler tends to resonate more with customers.”

Temelli added: “I think it’s important to divulge colour grades, depth and tones in relation to coloured diamonds more in-depth during the communication with the customer, as this gives value to the quality of the diamond.”

Individual fancy colour grades are quite wide, and the price difference between a weak and strong fancy intense diamond and can be close to double.

As previously mentioned, to grade fancy colour diamonds, laboratories such as the GIA use a set of master stones and the Munsell Book of Colours.

This is a colour chart of approximately 1,500 different shades and is particularly useful when suitable master stones are not available.

|  |  |  |

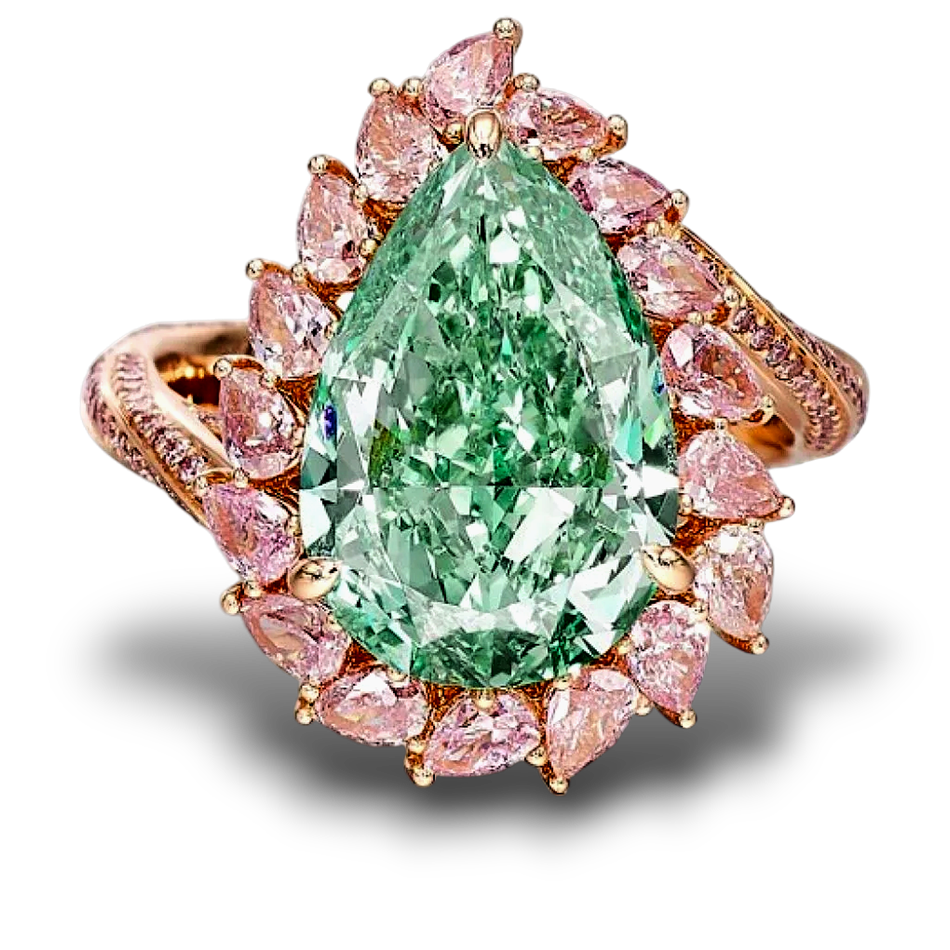

Williamson Pink Star The 11.15-carat Williamson Pink Star sold for $US57.7 million ($AU89.74 million) at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong in 2022. | Pink Star The record return for a pink diamond at auction remains with the 59-carat Pink Star, which was sold in 2017 for $US71.2 million ($AU110.73 million). | Sakura Diamond This 15.81-carat fancy vivid stone was sold to a telephone bidder in Hong Kong for $HK226 million ($AU37.7 million) in 2021. | Aurora Green A rectangular-cut fancy vivid green diamond, weighing approximately 5.03 carats, and set within a circular-cut pink diamond surround. Sold at auction in 2016 for $US16.81 million ($AU25.91 million). |

Evolution

Garry Holloway of Holloway Diamonds proposed a simple explanation for the evolution of vocabulary around the category.

“It’s possible that ‘fancy’ simply sounds boring or trite to many these days; however, it has a meaning and values are based on the words that come after,” he suggests.

Indeed, in terms of general use, the word fancy may have become somewhat outdated, just as ‘ladies’ is rarely used today when discussing ‘women’.

Holloway suggested that the declining use of the term when addressing consumers, particularly when in Australia, may stem from the introduction of a separate colour grading system at the Argyle Diamond Mine.

The GIA’s colour grading system was considered limited when it came to differentiating pink diamonds mined in Australia, and so the Argyle mine began to divide production into four separate categories – purple-pink, pink, pink-rose, and pink-champagne.

Within each category, the diamonds are further classified according to the strength of the colour, from the deepest most desirable colour (one) to the lightest (nine).

There was one exception - the pink-champagne category - which has only three strength ratings.

“I know that many online retailers have simplified the wording, such as the Signet companies, including Blue Nile and James Allen, as well as Brilliant Earth. Those are the three largest by far,” Holloway said.

“However, in their search criteria, they always use the GIA ‘fancy nomenclature’ names on the slider."

Rob Bates, news director at JCK Online, says that while the term ‘fancy’ is redundant, he doesn’t see the harm in its continued use.

“I agree ‘fancy’ is a bit redundant, but as we have seen many times, trade terminology and customs take on a life of their own, and can be hard to change,” he tells Jeweller.

“While I'm willing to entertain other opinions, the word fancy doesn't seem particularly misleading and could provide a point of difference vis-a-vis lab-created diamonds.

“It also goes along with the grades, such as fancy deep and fancy intense. All in all, it seems pretty harmless, and as long as everyone stays honest, I think it's fine to use, and fine to drop.”

Shubham Maheshwari, marketing director of Kunming Diamonds, agrees with Temelli and suggests that keeping it simple with consumers is always the best approach.

He also offered a possible explanation as to why major retailers are sticking with ‘coloured diamonds’.

“There are a few reasons why companies may choose to omit the word ‘fancy,’ he explains.

“By removing the term ‘fancy’, the language used in marketing materials is simplified, making it more straightforward and easier to understand for potential buyers.

“Additionally, companies may have identified that certain keywords or phrases related to fancy colour diamonds are not as effective in online marketing campaigns.”

Diamond industry analyst Ari Krawitz believes that there is a redundancy in the terminology; however, he suggests it’s necessary in order to avoid confusing consumers.

“I refer to coloured diamonds as fancy colour diamonds. In my mind that avoids any confusion around ‘fancy shape’ diamonds which are typically referred to as ‘fancies’, he explains.

“It probably is redundant in my view. With that said, as long as the description has the word ‘diamond’ attached, to avoid clashing with coloured gemstones, I’m happy.”

|  |  |

The Argyle Rose 1.36-carat fancy deep pink diamond

Solid Gold Diamonds | The Delaire Sunrise 221.81-carat fancy vivid yellow diamond

Graff Diamonds | Tzarina 2.15-carat fancy intense purplish pink diamond

Calleija |

| | | |

Keep the flame alight

Described by the Fancy Colour Research Foundation as ‘the most influential fancy colour diamantaire in the Far East,’ there are very few who can rival Ephraim Zion as an authority on these matters.

Zion’s career began in Israel as a diamond cutter apprentice at the age of 14. After relocating to the US, he became a highly sought craftsman in New York.

In 2008, he became a governor of the GIA, joining the organisation for nine years. Zion says that regardless of any redundancy, it’s important that the diamond industry upholds the ‘fancy colour’ terminology.

“If you were to look at the language from a logical point of view, yes, I would agree that it’s redundant. Common sense says it’s unnecessary,” he tells Jeweller.

“With that said, I think the current nomenclature is most suitable for these stones.”

Zion says that hypothetically should such a radical change in terminology occur, there would be a major hurdle to cross – namely, the second of the six grades, which is simply ‘fancy’.

If the word ‘fancy’ was eliminated due to redundancy, then that grade would need to be outright renamed – and finding the appropriate language is difficult. Should you eliminate that grade, the entire structure falls apart.

On the topic of language, Zion also drew attention to the GIA’s move in the 1990s to introduce the fancy vivid and fancy intense categories, suggesting that it was a positive example of the nomenclature evolving.

“It was necessary that the GIA create two new denominations to distinguish between fancy, fancy intense, and fancy vivid. It gave a more accurate representation of the colour differences between those three,” he explained.

“In 1995, the GIA realised the need for more accuracy. Before these changes, you needed to rely on your understanding of the saturation of colour and trust your eyes and experience when buying a stone.”

In 1971, Zion relocated to Asia and joined his family’s diamond and gemstone business. In 1985, he established the House of Dehres, a company that creates remarkable fine jewellery.

House of Dehres scours the world for high quality and unique gemstones, and then produces fine jewellery using its team of talented artisans.

“I have always loved fancy colour diamonds, and I’ve been very fortunate to be based in Hong Kong. Asian culture has always valued colour gemstones and fancy colour diamonds have always been appreciated here,” he says.

“That’s not always been the case in other places, where these stones have not always been revered the same way that they are today.

“I can remember when I was younger, seeing dealers handle parcels full of colour diamonds with little regard. That amazed me, peering inside and seeing small reds, greens, blues – all the colours of the rainbow – and these stones were given such little consideration! How things have changed.”

|

The Mouawad Empress 37.50-carat fancy vivid yellow diamond

SOLD US$2.7 million @ Sotheby's | Juliet Pink Diamond 30.03-carat fancy intense pink diamond

LJ West | The Blue Moon of Josephine 12.03-carat fancy vivid blue diamond

SOLD US$28.5 million @ Christie's |

| | | |

Learning from the legend

While the observation that many jewellers appear to be dropping the term ‘fancy’ is new, the debate about the language used around these diamonds is not.

Earlier this year, one of the world’s most revered diamond cutters, Sir Gabriel Tolkowsky, passed away at the age of 84.

The language used by the diamond industry was a topic close to the heart of Tolkowsky. In a presentation in Moscow in 2004 – organised by Holloway, among others - he addressed these matters.

“The internet and the multiple publications have resulted in our professional language on diamond grading reports spilling into common knowledge,” he said.

“Now, the general public attempts to use this technical and specialised language and knowledge. Is this appropriate for consumers? Will it result in them being more attracted to diamonds for their inherent beauty and symbolism?

“Or should we keep our professional language to ourselves and adopt other language that is more descriptive for the sense such as rarity, beauty, dream, emotion, craftsmanship, and art?”

During the presentation, he discussed the language used by cutters and polishers. Terms such as cut, cleave, brute, saw, and laser are common; however, when it comes to speaking with consumers, these terms are not used because they lack romance.

A consumer is not interested in a diamond that has been cut and cleaved. They’re looking for a diamond that has been divided, fashioned, and styled!

It’s important in all retail contexts that the appropriate language is used when dealing with consumers to prevent damaging the public’s image of products.

“So, can we imagine new terminology that better describes the diamond so that it means more, and adds better value, to what we have done with a natural rough gem?” asks Tolkowsky.

“The thing that was created by The Almighty, the creator of all things. What words can we give to diamonds to make it more beautiful and important and meaningful to the person that will buy it as a gift – perhaps the most important gift or symbol that many people will receive in their lives?”

Nearly 20 years ago, Tolkowsky was keenly aware of the importance language plays in the love consumers have for diamonds. He highlighted the significance of nomenclature and the impact that scientific jargon can have on the perception of a diamond.

Today, the diamond industry faces a similar conundrum!

The industry must walk a tightrope between protecting consumer attachments and prioritising language that is simple and easy-to-understand, while also adhering to a thorough scientific understanding of what it is that makes these stones special. After all, it’s the mystery and intrigue behind fancy colour diamonds which has made them so very valuable – and not our scientific understanding of the stones themselves.

And if we consider that language evolves, and it's common for the change to relate to technological advancements, what are we to make of a colour or coloured diamond?

Do those two terms mean the same thing? Or should they be used differently because ‘coloured’ could imply, or at least sounds like, the diamond was artificially treated to enhance the colour?

It might be a case of semantics but isn’t that what nomenclature is all about? That said, we will leave this debate for another time!

Read eMag